I am a Gambian and an American citizen. My dual citizenship bears civic responsibilities and rights in the two countries. I am invested in both the country I was born in and the country I live in, as hundreds of thousands of other Gambians live and work outside our country of birth.

The current globalised reality has created dual and multiple citizenships that obligate citizens to water the tree from which they receive the daily shade and to nourish the distant soil that raised them because they still have loved ones there.

However, most importantly, our identity is rooted in that distant soil, a more powerful belonging than the foreign residence that becomes a new home.

The path to the Gambia’s nationhood has been ridden with the marginalisation of communities that now include the Gambian Diaspora. Marginalisation does affect not only communities under economic distress but also those whose political rights have been suppressed.

For a long time, geographical marginalisation has always been reserved for those in the Gambian Diaspora community.

However, the Gambia Diaspora community no can longer ideally be considered a marginalised community now because it is economic power base, notwithstanding, the Gambians in the Diaspora were reported to have remitted up to $182 million in 2018 or 22 percent of GDP (World Bank World Development Index,2019 ).

This made the Gambia the third largest in Africa and eighth most extensive in the world (again, as a share of GDP) from Diaspora remittance to the Gambian economy which is far greater than what the Foreign Aid and Development Assistance contributed by the international community’s donor funding and grants towards the Gambian economy.

In nation-building, no real unity is ever achieved until all communities that are part of that nation are accorded equal realisation of their rights. The discrimination of citizens using geographical location has historically affected the communities in other rural areas, driving them to extreme socio-political and economic marginalization.

This discrimination has become a reality for the Gambians in the Diaspora, notwithstanding this constituency’s economic and political clout.

Voting leads to the right to representation, which lends a voice to communities that might not otherwise be heard. It is this voice of the right to vote that the Gambians in the Diaspora seeks. Voting is the most powerful of political rights, giving every individual citizen an equal voice regardless of ethnicity, religion, gender, or wealth.

The Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) must work with the Diaspora community to vote in future elections. One of the excuses the IEC has repeatedly used is that it does not have reliable Gambians’ statistics in the Diaspora.

There has been zero political will to create productive partnerships. Change can come through one person with a hundred of thousands of dollars or through a hundred voices with one purpose. The platforms that the Diaspora has created can be used to raise a hundred of thousands of voices.

Since independence, Gambian Diaspora has been a forgotten population because it is a politically disenfranchised constituency, having been denied the right to vote not enshrined in the Constitution.

Political exclusion, like any form of marginalisation, implies the suppression of rights. The Gambia Diaspora has an active history of the struggle for inclusion dating back to the millennium turn. It started with the push for dual citizenship activism and political civism.

Gambians seeking higher education or economic refugees, especially in Asia, Europe, North America, and elsewhere, and who had settled there with their families began to understand that they were here for the long-haul and needed to secure a structured belonging as transnational citizens.

Gambians learned from Diasporas who had settled in the US for decades that no matter how long they stayed away from home, they still pledged allegiance to their home country. The Jewish, Irish, Filipino, and other Diasporas in the US have become influential contributors to their home countries’ political and economic wellbeing while still maintaining active participation as citizens of the United States. The concept of transnational citizens, as advocated by Diaspora Gambians, was alien to many.

The Diaspora has actively been involved in numerous relief efforts whenever there was a disaster in the Gambia — from floods to civic engagement, philanthropic, and scholarship funds — efforts that speak of connectedness with home despite the distance.

The Diaspora community is growing, and the government must address the issue of political exclusion. Opportunities to make this viable between the government and the Diaspora are there.

Through the Diaspora groups, these Gambians have pushed for acknowledging the Diaspora vote through online petition processes and have the right to registration and voting mechanisms.

The Independent Electoral Commission gets its funding from the government and foreign donors, including the United Kingdom, the United States, Denmark, and Norway. The failure to budget for hundreds of thousands of Gambians’ constituency is not just negligence; it is discrimination and electoral fraud.

One solution to resolving the political inclusion stalemate against diaspora voting is for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the IEC to recognize the Diaspora’s solutions, such as creating partnerships.

A Gambia constituency that remits over 22 percent of the economy’s GDP disenfranchised and lose the right to vote under incompetent laws is unthinkable in a normal democratic society.

Moreover, it is also from the Gambian Diaspora community that the Gambia government has been scheming to find the money for padding the treasury, without recognizing the Diaspora community civic engagement rights.

Diaspora voter inclusion is an imperative that would strengthen the sense of nationhood and attract investment from an endowed constituency seeking to play a role in nation-building.

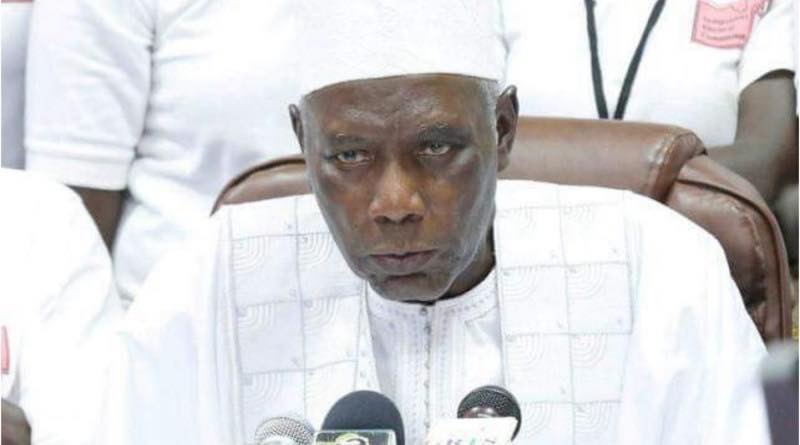

The chairman of the Independent Electoral Commission, Alieu Momar Njai, in a press statement, revealed that Gambians’ voting rights in the Diaspora and shall be represented in the National Assembly in the short-term.

However, the executive’s political will to translate such a commitment to substantive political and electoral reform into policy action will demonstrate high voter participation. It can level the electoral playing field to deliver democratic change.

However, beyond politics, it is a good idea on the merits. In our Constitution, it would enshrine a principle that we already believe that the right to vote and be represented in the National Assembly is an inherent attribute of citizenship and a cornerstone of civic equality.

In reality, the Gambian Diaspora community is a forgotten population because it is a politically disenfranchised constituency, denied the right to vote, as enshrined in the Constitution. Not once, not twice, President Adama Barrow must consider the Diaspora as his constituency.

He repeated that assertion again and again. Perhaps he should remember that the entire country and Diaspora Gambian was his constituency in the 2016 Presidential Election – and maybe in 2021 general elections.

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Recent Comments