On a sunny, humid day in April 2017, a plane carrying 170 Gambians from Libya touched down at the Banjul International Airport. First to step onto the tarmac – after four months of hardship in Libya’s capital and an even longer journey to get there – was Fatou. In her arms was a 3-month-old baby, safely wrapped in a white and pink-coloured cloth. The baby was not hers.

“I helped my friend by carrying her baby out of the plane. People saw me with the baby and thought that he was mine,” Fatou recalls. “They just assumed I had a child in Libya. Even if I did, they shouldn’t have judged me for it.”

The questioning glances she received on this, her first few minutes back home, was but a taste of the lukewarm reception she would receive over the coming months.

Fatou Bojang is among 5,000 Gambians who have been assisted with voluntary return home by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), through the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migration Protection and Reintegration, with support from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. As their conditions in Libya and on the migration routes worsened, many of them sought IOM’s assistance to return home.

Unemployment? Crime? Substance abuse? Mental illness? These are some of the narratives unfairly associated with returnees. This was certainly true in 2017 when hundreds were returning home each week to a Gambia that had just emerged from the shackles of a 23-year authoritarian regime and faced an uncertain future.

For Fatou, her act of kindness to a friend’s baby would sour into the smearing of her character. For months, she fought against the stigma –combatting rumours she had returned home ‘empty-handed,’ yet with a baby in her arms.

With word spreading across her community, Fatou’s health took a turn for the worse. She began battling persistent stomach aches. Constant visits from her friends, who pried and pried about the details of her journey, did not aid her wellbeing.

She was bitter at first. Bitter that her dreams of reaching Europe shattered. Bitter about all the unfair rumours being spread simply because she carried her friend’s baby out of the plane. Bitter that she did not meet society’s benchmark for a ‘successful’ migration story: reaching Europe and sending remittances back home.

All she ever wanted was to make a better life for her family. Yet, even as her physical and social conditions deteriorated, Fatou’s journey home was transformed into a journey of recovery.

Her turnaround began when she received support and encouragement from family members, many of whom initially had mixed feelings about her return. Realizing the relief her family had in seeing her home again—and alive—confirmed that she had made the right decision.

From that point on, her strength began to grow, building on a newfound self-confidence.

“Others used to say a lot of negative things about me. But now I can ignore them, because I know my story and what I went through,” she states.

Fatou soon opened, with the support of IOM, a cosmetic shop in her hometown of Tallinding, 13 kilometres from the capital.

The enterprise gave her a lift. Business was booming, and savings accumulated. She would buy cosmetic products—creams, perfumes and wigs—in bulk, then resell them at rates cheaper than other vendors’. On top of this, her strategic business location gave her a profitable advantage.

“The business helped me a lot,” Fatou explains. “I started to earn a decent living and began helping my family and other relatives.”

Shortly thereafter, she and fellow returnees put into action a plan they hatched while in detention together in Tripoli. They established a returnee-led association – the Youths Against Irregular Migration (YAIM) – to share their stories to the nation.

They knew first-hand how misleading information can lead one to such perilous migration routes. They pledged to fill this information gap when they returned.

Together with YAIM, Fatou began touring the country, meeting youth, potential migrants and their families and engaging with them to pursue alternatives to irregular migration.

“My involvement in these activities really boosted my spirits,” Fatou says. “Sharing my story helped me resist the negative perceptions I faced.”

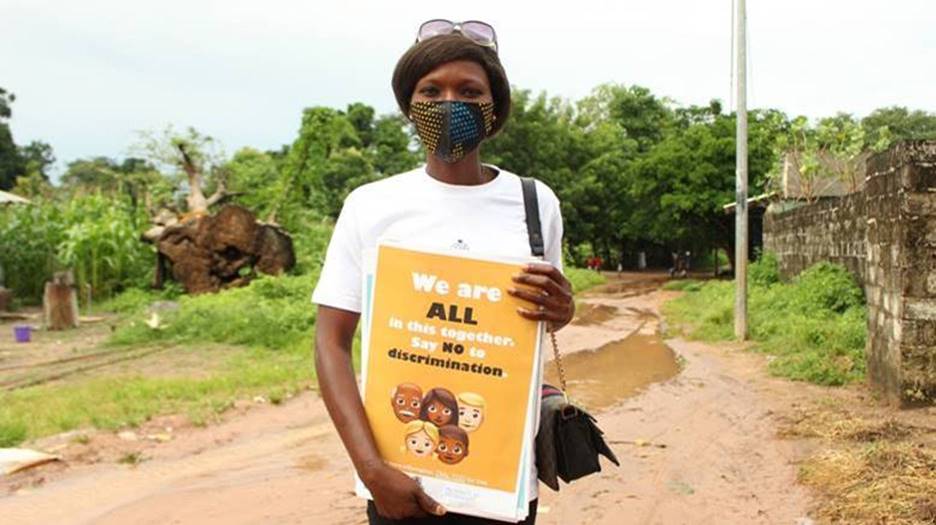

These days, she and her fellow returnees are using their voice and strong nationwide network to combat COVID-19 misinformation and discrimination.

Fatou recalls one serendipitous encounter in one of many awareness raising activities. “I was talking about a friend, Saikou Jabbie, who died in the Mediterranean Sea when the boat he was on capsized. I did not know his mother was in the audience. She suddenly came to me, hugged me with tears and asked me how I knew her late son. It was so emotional.”

For Fatou, the fulfilment of the recovery process is linked with helping others. Through community engagement initiatives, Fatou finds strength in returnees inspiring and empowering each other. Through hearing fellow returnees’ stories, she finally feels that she is not alone.

It now has been over three years since Fatou returned from Libya, demonstrating the point that, oftentimes, mental and psychosocial recovery can be a lengthy process.

Today, just like anyone else living in the world of COVID-19, Fatou faces unexpected hardship. Border restrictions between The Gambia and Senegal have taken a toll on her business. “The person I buy my wholesale products from is stranded in Senegal. Now, all the products I had in store are sold,” she laments.

Despite this, Fatou remembers what she has been through and that she has survived worse. She is optimistic that life will go back to normal soon to allow her to reignite her business.”

Grappling with these struggles, Fatou still has fresh memories of her friend, Saikou, and the last words they shared before he left. “He visited me and said, ‘Tomorrow at 11PM, I will take the boat to Italy. I will call you when I reach there.’ I prayed for him and wished him luck.”

She finds solace in the gift of life, knowing that she would have been on the boat that capsized if she, like Saikou, simply had had enough money to pay for her journey.

Fatou’s return and reintegration was made possible through the EU-IOM Joint Initiative for Migrant Protection and Reintegration, under which over 5,200 Gambians have voluntarily returned home since 2017. The project supports the reintegration process of returning migrants through an integrated approach, which addresses economic, social, and psychological dimensions.

Fatou is a member of the Migrants as Messengers programme, through which a network of returnees employ peer-to-peer communication to help people make informed migration decisions.

This story was written by Saikou Suwareh Jabai, IOM’s Communications and Awareness Raising Assistant in The Gambia.

One Comment