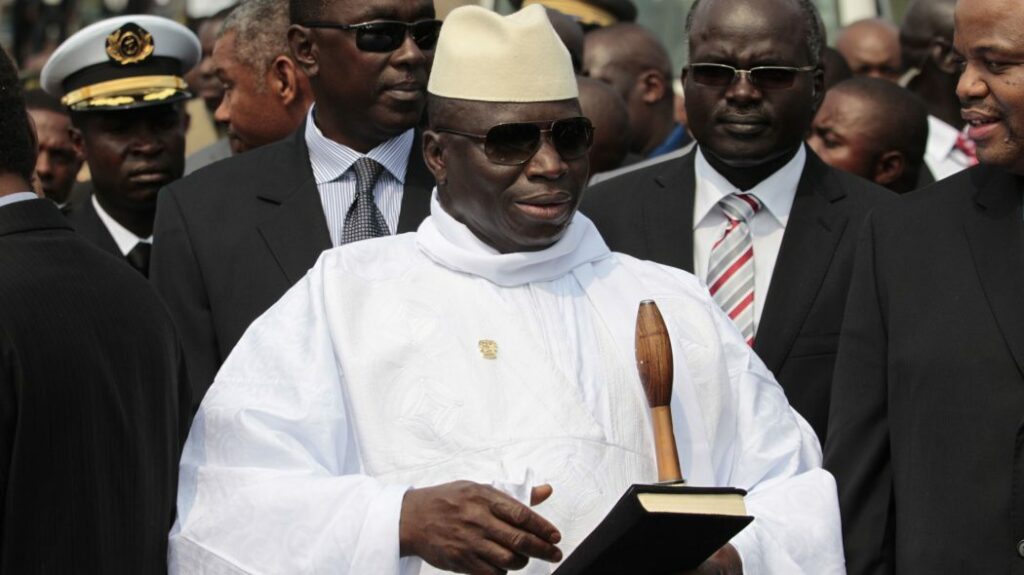

In the aftermath of Yahya Jammeh’s 22-year reign of terror, The Gambia stands at a moral crossroads. The pursuit of justice for the atrocities committed during his despotic rule has been selective at best, targeting Jammeh himself and a handful of his closest allies.

But what of the many others—the scholars, intellectuals, and senior officials—who knowingly enabled his tyranny? These individuals, once complicit in the machinery of oppression, now find refuge within the opposition and civil society, their pasts conveniently sanitised and their roles in Jammeh’s regime quietly overlooked.

This glaring double standard raises profound questions about the integrity of The Gambia’s transitional justice process. How can a nation truly heal when accountability is applied unevenly, leaving the architects of oppression to reinvent themselves as champions of democracy?

What does this selective reckoning reveal about the hypocrisy embedded in our collective pursuit of justice? And on a deeper moral level, how do we reconcile the actions of those who, despite knowing Jammeh’s tyranny, chose to serve his regime, only to later seek absolution through political realignment?

The answers to these questions are not just a matter of historical record—they are a test of The Gambia’s commitment to truth, justice, and genuine reconciliation.

As we confront the legacy of Jammeh’s rule, we must ask ourselves: is this a reckoning, or merely a reshuffling of power?

A Gambian court has delivered a landmark verdict, sentencing former intelligence chief Yankuba Badjie and four other members of the intelligence service to death for the brutal murder of political activist Ebrima Solo Sandeng during Yahya Jammeh’s oppressive regime.

This decision marks a significant step in addressing the atrocities committed under Jammeh’s rule. In a striking parallel, Yankuba Touray, a former minister, has also been sentenced to death for the heinous killing of his fellow minister, Koro Ceesay—a crime that epitomises the ruthlessness of Jammeh’s administration.

Both cases reflect the enduring legacy of Yahya Jammeh’s dictatorship, where a culture of impunity allowed atrocities to flourish unchecked. These verdicts underscore the urgent need for accountability and justice to right the wrongs of the past.

Yet, they also expose a glaring inconsistency in The Gambia’s transitional justice process: why did these individuals, implicated in such grave crimes, fail to appear before the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Commission (TRRC)?

The TRRC, envisioned as a platform to uncover the truth, foster reconciliation, and address past injustices, has primarily focused on a select few perpetrators while overlooking others who enabled Jammeh’s reign of terror.

This selective approach raises critical questions about the principles and spirit of the TRRC compared to similar commissions globally.

These cases reveal a deeper dilemma within The Gambia’s pursuit of transitional justice: how to reconcile retributive justice—focused on punishment for perpetrators—with restorative justice—centred on healing and reconciliation.

As The Gambia continues to navigate this complex path, the absence of individuals like Yankuba Badjie and Yankuba Touray from the TRRC process leaves an unsettling void, both in the collective reckoning with the past and in the pursuit of a truly inclusive national healing.

Yahya Jammeh’s dictatorship was not an isolated episode; it was a systematic government policy involving numerous individuals within his regime, all complicit in human rights abuses and gross mismanagement.

Why focus solely on prosecuting Yahya Jammeh or a select few of his associates when the majority of atrocities were carried out with the active participation of many? Alarmingly, some of these individuals still occupy positions within the government, despite their dark past.

Even more troubling, many former officials from Jammeh’s regime, who played significant roles in these egregious acts, are now embraced by the opposition and civil society.

They receive unwarranted praise and a false sense of absolution from their crimes. This raises a critical question: what is the real purpose of prosecuting Yahya Jammeh if accountability does not extend to all those involved?

Sacrificing peace or justice?

Justice or peace? That’s the crux of the debate. Since the enactment of the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Commission (TRRC), Gambians have grappled with how to heal a divided nation—politically, ethnically, and emotionally.

The question of whether amnesty and forgiveness are appropriate strategies has sparked widespread debate. With so many divergent voices weighing in, it’s anyone’s guess where President Adama Barrow will ultimately land following the TRRC’s report and recommendations.

There is no doubt that the former cronies and associates of Yahya Jammeh’s regime, along with other extremists fueling this debate, are a mob of depraved zealots who committed heinous crimes against innocent people—women and children who had done nothing to deserve such cruelty.

Under any structure or belief system, there must be retribution. Criminal prosecution is a fundamental aspect of a victim’s right to justice. However, remedial justice often has to be balanced against the need to prevent further violence.

In such circumstances, a restorative justice approach incorporating amnesty may be the more appropriate model. This is where the issue of amnesty for Yahya Jammeh and his enablers comes into play.

Historically, amnesty has been employed as a means of promoting settlement and advancing reconciliation in societies emerging from repression. While it is a tool often utilised in conflict resolution, it has never been viewed as the best option—only a necessary one.

When atrocities are committed with impunity, as in the case of Yahya Jammeh and his regime, forgiveness and restorative justice alone cannot legitimise the concept of human rights. A carte-blanche amnesty for the APRC government, despite the mass murders and butchering they subjected innocent Gambians to, falls short of this standard.

The debate over amnesty for Yahya Jammeh and his accomplices boils down to a choice between peace and justice. Ideally, any strategy should incorporate both concepts.

But in the context of the atrocities committed, amnesty may offer the best prospect for peace—not justice. Unless Gambians surrender to hypocrisy and forgiveness, peace and justice cannot coexist in this case. If a single choice must be made, what should we prefer?

A battle of conscience

For me, this is a battle of conscience—a struggle between the past, the present, and the future. The past demands justice for the victims and accountability for the crimes committed. The present calls for peace and reprieve for innocent people caught in the storm.

But the future poses the most critical question: which option—peace or justice—has the ability to fundamentally change the status quo and provide a stable and secure future for Gambians?

History shows that peace deals sacrificing justice often fail to produce lasting peace. Justice, on the other hand, creates structural change that prevents a return to conflict. While justice may be a long and winding road, it offers a more sustainable path to reconciliation.

Yet, the quest for justice can exacerbate divisions and hinder peace. Amnesty, though sought at the expense of retributive justice, is often thought to promote peace and reconciliation.

The government must gauge the views of those most affected by the violence—the communities, families, and businesses residing in the red zones. Their cries and anguish, not the opinions of politicians or dogmatists, should guide the decision on amnesty.

Full reparations must be provided to victims and their relatives. Any initiative should balance the demand for justice against the need for peace and reconciliation.

While accountability provides justice and amnesty offers stability, achieving both is nearly impossible. A choice must be made.

As we unravel the dark legacy of Yahya Jammeh, the choice is not about which criminals deserve amnesty or which don’t. It’s not about allegiance to ethnicity or religion.

It’s about what we are willing to sacrifice: justice for the cause of peace, or peace for the cause of justice? Over to you, President Adama Barrow—what will it be: peace or justice?

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Recent Comments