Over the course of my long career I developed many sources in the Gambia intelligence apparatus, on top of that I infiltrated the corridors of power in the Quadrangle buildings, Marina Parade and staffers in the State House.

In addition, to leaks arising out of “appropriately” from court papers, National Assembly members; also leaks from State counsels, besides judicial assistants, including some cabinet ministers as well as members from the bar and the bench.

Though these operatives and top senior civil servants rarely much agreed with me ideologically, philosophically and politically, they came to respect and trust me, because they knew that I would honestly use any information they gave me, and that, if they promised to protect their identities, I would do so. In some cases, these relationships led to life-long friendships.

Ideal journalists are a special breed. They see the world as theirs to mold in the image of whatever is good and desirable. They are vulnerable and at the same time impregnable. They do not worship in the shrines of gods that fight the helpless. They are guardian angels of those things classified as public good.

A veteran journalist once immodestly described journalism as the best job in the whole world. But a true journalist has very few friends. He is not a fool; he knows. He knows the flashes of smiles that receive him in places his assignments take him are crocodile smiles. He knows the work he does opens doors for him and in equal measure, closes doors against him. He knows the society merely tolerates him and silently wishes he would quietly vanish into the dark of the night.

When I was being interrogated about my sources for the story on presidential corruption and human rights violations, I knew that my reporting was in the best tradition of a free press, the kind of journalism that civilized societies seemed interested in promoting in their society.

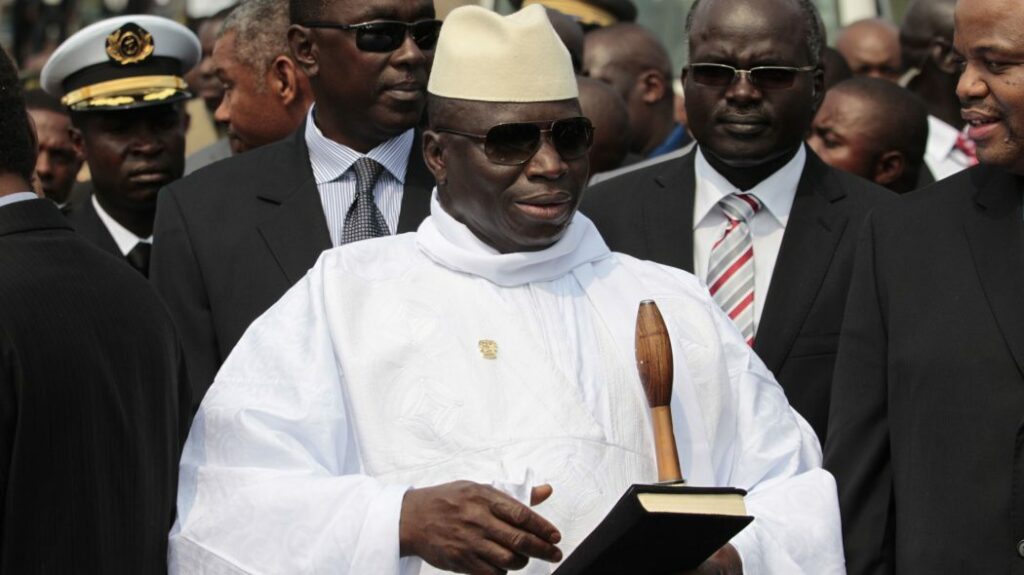

The harassment and imprisonment of journalists in the Gambia during Yahya Jammeh’s despotic rule sends a bad message globally, where press freedom has been under attack for a long time. Journalists lamented the fact that the Gambia was no longer a beacon of hope for press freedom.

During Yahya Jammeh’s regime whistleblowers were silenced, journalists cannot protect their sources and investigative journalism stymied by law enforcement agents.

I was dazed when the Inspector General of Police, Famara I Jammeh together with his boss Major Momodou Bojang, Minister of Interior, condone and encouraged enhanced interrogation actively involving scapegoated junior officers, this happened on their watch at the Interior Ministry unknowingly instilled fears into me.

However, Police Superintendent Jatta Baldeh with two of his junior officers, Ceesay and Cham, menacingly brandished a weapon in an angrier and threatening manner. “Get ready to be circumcised,” Superintendent Baldeh’s men yelled out to me as they walked towards me cultivating manliness and bravado in front of their superiors, and being weak, and the high value on physical toughness, they threaten to circumcise me for refusing to divulge the name of a confidential source.

I was recalcitrant and obstinately uncooperative to the police intimidation since I am entitled to statutory and constitutional protection for confidentiality. It may be convenient for the police to force journalists to reveal sources but for journalists, it’s not right for freedom of the press and its not right for the whistleblowers. I argued this point with them and remained obdurate

For me, the fact that kind of threat was on their watch, the Minister with top senior officers of the Gambia Police Force, was a shock in itself. The look on their faces left no doubt that they were capable of carrying out the threat. Those fears were so deep in my subconscious that I didn’t realise or even deal with them until today. Now that I am a father.

The Interior Minister, Major Bojang, Inspector General of Police, FRI Jammeh along with, Police Superintendent Jatta Baldeh frightened and their minds in a turmoil, was stone-faced men. Mr. Momodou Aki Bayo, Permanent Secretary at the Interior was watching and holding a notepad jotting notes for his boss while Police Inspector Mam Bojang together with two other low-ranking officers, Ceesay and Cham acting like a zombie lacking the brain power to delay gratification. The looks on their faces left no doubt in their minds that at some stage the encounter would develop into a violent and vicious confrontation

All this happened when the Inspector General of Police and Minister of Interior ordered for my immediate arrest and detention about a lead story I had published in my newspaper, The Independent, on presidential corruption and human rights violation. I was briefly held at the Serious Crime Unit at the Banjul Police headquarters where I was interrogated about my sources for the story. The police demanded that I write a statement disclosing the source of my information. I refused. They threatened to send me to jail if I did not cooperate. At the Serious Crime Police Inspector Mam Bojang led the interrogation and was assisted by two other police officers in Mufti.

I was informed that the Serious Crime Unite of the police already knew who had given me the information and all of my sources for my previous publications. I was later escorted to the Ministry of Interior to meet with top brass of the Gambia Police Force.

The Inspector General of Police, FRI Jammeh said: “I knew your sources and your informers”. I answered in the negative. I was told to accept that my stories are false news as well as to reveal my sources about the headlined story “Hunger Strikes and Prison Riots at the Mile II” reported by the British Broadcasting Corporation and carried by the local papers.

When I maintained that was not true, I was subjected to further verbal assaults and intimidation from the Interior Minister and the Inspector General of Police. I was calm and steady in the conference room upstairs at the Interior Ministry where I was being held and asked to identify and reveal my sources as well as of those of informers.

I again refused to incriminate anyone and was taken back to a brightly lit office waiting for any action. The Inspector General of Police, FRI Jammeh, police superintendent Jatta Baldeh together with other officers appeared in the room and telling me that I had little option but certain jail time if I did not cooperate by accepting to reveal my sources.

When I refused to reveal my confidential sources, I felt that there are some ethical considerations for a journalist, protecting sources is essential. Many have even gone to prison to defend these relationships, knowing quite rightly that whistleblowers will not talk to them if they know their details can just be handed over.

But, shockingly, it seems the police have been engaging in wide scale targeting of journalists. They obtained the phone records and personal computers, notebooks and many others to view journalists records to identify their sources.

This is unacceptable. It risks jeopardising investigative journalism and freedom of speech. How will anyone be brave enough to contact a journalist in the public interest, if they know that they can easily be tracked down?

What’s more, these actions have clearly discouraged whistleblowers from coming forward, having a chilling effect on free speech. In the Gambia during the heydays of President Yahya Jammeh’s administration the police quite wrongly, without a judge’s approval, used coercion and abuse against journalists. They authorise themselves to ask the journalists to reveal their sources and other communications data. This cannot be right.

For example, on 8 July 1998, Serekunda police arrested and interrogated me about a lead story I had published about prison conditions. The police demanded that I write a statement disclosing the source of my information. I refused. They threatened to send me to jail if I did not collude. For me, this was nothing new. The police and the National Intelligence Agency have arrested, detained and interrogated me several times.

During my detention for refusing to disclose my confidential sources in the investigation into leaks of a hunger strike at the Mile II Central Prisons. Police Superintendent Jatta Baldeh called my elder brother, who was then a senior police officer to persuade me to disclose my sources in exchange of my freedom from police custody. I refused. And police forced me to write a statement? I wrote on the cautionary statement, which I believed in could be held against me in court and it reads: “My sources are the Inspector General of Police, Famara I Jammeh and Station Officer Jatta Baldeh of the Serekunda police station”. I signed and handed over my cautionary statement to two police officers escorting me.

Conversely, having read my statement, Superintendent Baldeh shook his head in disbelief and gave a faint supercilious smile, as though in total disbelief of words. He released me immediately and unconditionally without charged. This was how I escaped police prosecution for refusing to disclose my confidential sources in another instances of police harassment.

As a matter of principle, police and security services should not be able to authorise themselves to snoop on journalists to get to their sources. It may be convenient for the police but it’s not right for freedom of the press and it’s not right for the whistleblowers who badly need protection.

It further strengthens my argument that if the government feels sufficiently aggrieved, it should have reported to the Gambia Press Union or use the courts instead of resorting to police harassment, which has never worked in the county.

I find it strange that the police were asking for the source of the information of the journalists and Gambian police gloating that the police are doing their job. I can’t believe this. Even a cub reporter knows that a strong, cardinal principle in journalism is the protection of your source of information, even at the point of death.

Investigative journalism has proved itself as a valuable adjunct of the freedom of the press, notably corrupt and human rights exposure in the Gambia and the mega sleaze exposure in this country. It should not be unduly hampered or restricted by the law. Much of the information gathered by the press has been imparted by the informant in confidence.

If a source is guilty of a breach of confidence in telling it to the press. But this is not the reason why a source name should be disclosed. Otherwise, much information that ought to be made public will never be made known.

Likewise, with documents. They may infringe on copyright. But that is no reason for compelling their disclosure, if by so doing it would mean disclosing the name of the informant.

The Gambia Police Force are not a band that pampers the enemy nor is it a pride of lions that raids and sells its members to rival predators. It is not a bobo nice and it does not pretend to be nice. It is not meek and is not pretending to be gentle. It won’t lose coming after critics and it won’t agree to any loss. The same goes for Yahya Jammeh’s regime hostility towards journalists. Jammeh was young and inexperienced, but he was not stupid. He was not tired of being president like someone he upstaged. He has no ambition to become a martyr and therefore won’t offer himself to be nailed to the cross for some ill-defined democracy. He was born to lead, to rule and that has been his portion since the beginning of time, a dictator.

President Jammeh and his Interior Minister in the heydays, Major Momodou Bojang a very brilliant man. He can, in one short sentence, deliver a thick brew of sarcasm and satire and irony and other ingredients of hemlock for the side he chooses to fight.

That is why the ball was always pushed into Journalists penalty area knowing it would finish the job for the enemy. It set up draconian media laws but never knew how to use those weapons to catch the very many pilferers in the other house. The laws it made were very useful in fighting domestic wars and effecting seasonal in-house cleansing and purging. The AFPRC/ APRC was that foolish. It has power and does not know how to use it to grow its net worth.

You are preparing for a war and you think it is a winning strategy to give your armour to the enemy. Who does that except the one who is tired of everything? Before my arrest, I had not heard of a human being opting for suicide as a short-cut to being loved and canonised by his enemies. Those serving Yahya Jammeh loved his foes so fondly that even they loudly announced their shock at his lion turning out a lamb.

Yahya Jammeh’s market was full, he boasts and dares anyone to hold an opinion that puts a lie to his. That is the world of strongmen. Writing in Time magazine in May 2018, Ian Bremmer said humanity has arrived at the shore of puritanical macho leaders: “In every region of the world, changing times have boosted public demand for more muscular, assertive leadership. These tough-talking populists promise to protect “us” from “them.” Depending on who’s talking, “them” can mean the corrupt elite or the grasping poor; foreigners or members of racial, ethnic or religious minorities. Or disloyal politicians, bureaucrats, bankers or judges. Or lying reporters. Out of this divide, a new archetype of leader has emerged. We’re now in the strongman era.”

Yahya Jammeh fits right here. He was saving us from the past – all the past – except his own part of the past. If you ask him, he will beat his chest and say billion years from now, his mountain will be in the State House, immovable. And that will be because strongmen don’t lose elections, they don’t quit – even with court orders- they stay. They don’t go home; power is their home.

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Editor’s note:

This article is part of a portmanteau series titled “Me Yetti Allah I Lived to Tell …” by the former managing editor of The Gambia’s Independent newspaper, recounting his experiences of persecution and abuse by the former Jammeh regime.

Recent Comments