Long Read

The underlying idea is that societies need to confront and deal with unjust histories to establish a qualitative break with that past, and proponents of modern truth commissions thus “look backward,” not as interested historians, but as a way to “reach forwards.”

As Archbishop Desmond Tutu explained in his foreword to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) report: The Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission (TRRC), meanwhile, has been credited by many with persevering to “wake the Gambia up” from a long slumber of denial, helping the country put historical events in the proper light and order, revealing that Gambians themselves were capable of committing heinous crimes on their fellow Gambians while keeping a historical record of, preserving, and memorialising such horrific experiences.

The Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparation and Reparation Commission (TRRC) emerged in December of 2017 through an Act of the National Assembly, receiving presidential assent on January 13, 2018.

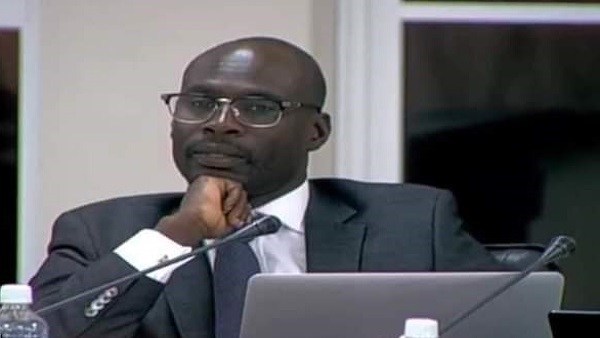

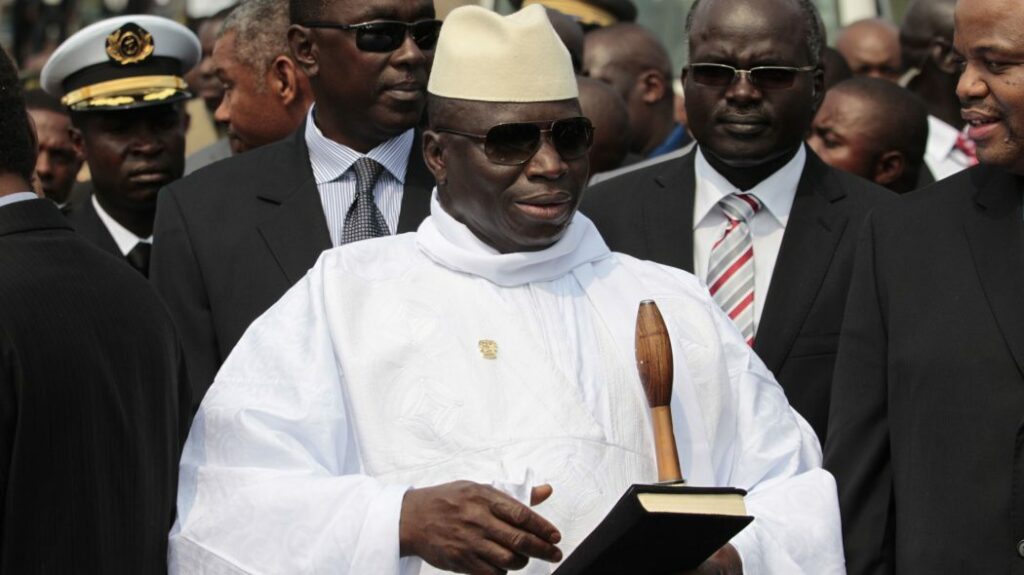

Officially launched in October of 2018, the 11-member Commission to investigate former President Yahya Jammeh’sJammeh’s era of human rights violations from 1994 to 2017, led by the chairperson, Dr. Lamin J. Sise and concluded its public hearing after hearing testimonies from 392 witnesses, the majority of whom were victims of atrocities meted out to innocent civilians by the State, its agents or individuals sponsored by both. The witnesses also included confessed perpetrators.

According to the Standard newspaper edition of March 18, 2022, the TRRC Amnesty Committee has “approved” amnesty from prosecution for former AFPRC vice-chairman Sana Sabally who admitted responsibility for killing many soldiers accused of a coup plot in 1994.

The ‘committee’s report, which was submitted to Justice minister Dawda Jallow, also “approved” amnesty for Major Bubacarr Bah and Zakaria Darboe. In addition, former soldier Alagie Kanyi was referred to the Ministry of Justice for “finalisation of immunity.”

The Standard newspaper meanwhile reported that the country’s former vice president, Dr. Isatou Niie-Saidy, has been denied amnesty from prosecution along with seven others and are among people adversely mentioned by the TRRC who applied for clemency to the Amnesty Committee following the submission of the TRRC Report, which recommended the prosecution of specified categories of people found responsible for grave crimes.

“All these applications were reviewed to determine whether or not they met the conditions for granting amnesty,” the report stated.

The newspaper further reported that about a dozen people’s applications for amnesty were dismissed. After all, some did not need to apply for amnesty because they were not recommended for prosecution or were only banned from holding public office, among other reasons.

The report also explained that the reasons behind each category’s decisions for the dismissed applications were based on the following reasons: “(i) The applicant(s) were recommended for banning/from holding public office and not to be prosecuted. (ii) The letter sent was a rebuttal of witness testimony and not an application for amnesty(iii) The committee determined that the applicant should not have been listed as a perpetrator as it was a case of mistaken identity.”

However, the applications that were denied amnesty were also based on the following reasons: “(i)The applicant(s) did not give full disclosure in their statement submitted to the Commission; did not give full disclosure in their testimony during the public hearing or did not give full disclosure in their application for amnesty.

(ii The applicant(s) were not truthful in their statement submitted to the Commission; were not truthful in their testimony during the public hearing or were not truthful in their application for amnesty.

(iii) The applicant(s) did not show remorse in their statement submitted to the Commission; did not show remorse during their testimony in the public hearing or did not show remorse in their application for amnesty.

(iv) The applicant(s) did not sign/endorse their amnesty application. Notwithstanding, a determination was made on the merits of the applications.

(v) Their acts or conduct form parts of crimes against humanity

(vi).The applicant(s) is one of those who bear the greatest responsibility. Therefore, granted applications applicants granted amnesty were based on the following reasons:(i)The applicant(s) gave a full disclosure in their statement submitted to the Commission; gave a full disclosure during their testimony during the public hearing or gave a full disclosure in their application for amnesty”, according to the Standard.

The other reason amnesia will not do is that the past refuses to lie down quietly. It has an uncanny habit of returning to haunt one.

However painful the experience, the past wounds must not be allowed to fester. They must be opened. They must be cleansed. Moreover, balm must be poured on them so that they can heal. This is not to be obsessed with the past. Instead, it ensures that the past is properly dealt with for the future.

Motivated by this desire to render the past “passed” in the definite sense of being “dead” or “over and done with,” modern truth commissions dedicate most of their time to two activities: the holding of public hearings and production of a final report.

This is a relatively recent development. Early truth commissions did not hold public hearings and were largely fact-finding bodies.

However, ever since the South African TRC of the 1990s, truth commissions have held hearings as a stage for various actors – victims, perpetrators, political parties, state institutions, and so forth – to present their accounts of past wrongs.

The underlying idea is that people will have a chance to speak and be heard, and thus regain their humanity; that a more comprehensive (and engaged) audience will bear witness to a new human rights-conscious regime; and the overview provided will feed into, and help legitimise a final report.

The latter, in turn, intended to record and acknowledge past wrongs and provide recommendations that can help promote truth, justice, reparation, and reconciliation.

However, while much hope is often placed, and much time and money expended, on truth commissions and their hearings and final reports, it is evident that these processes generally fall far short of ambitious goals and high expectations.

However, what explains this gap between aspiration and reality? This is one of the questions that are in a book, “Performances of Injustice” by Gabrielle Lynch, published on August.8, 2018: The politics of truth, justice, and reconciliation in Kenya– which provides similar situations analyses of several transitional justice mechanisms in other countries including the Gambia introduced truth, reconciliation and reparation commissions following years of injustices and human rights abuses.

However, following eight hundred and seventy-one days, Gambians through the Truth, Reconciliation, and Reparations Commission (TRRC), began a unique process of holding live public hearings of the testimonies of the victims, as well as those of confessed perpetrators of human rights violations and abuses that occurred in The Gambia during the twenty-two-year military dictatorship of President Yahya Jammeh.

The principal purpose of the truth commission was straightforward: to establish the truth of what happened during the twenty-two-year reign.

The National Assembly of the Republic of The Gambia enacted a law (TRRC Act, 2017) that established the TRRC.

The main objectives of the Commission are, among other things, “to (a) create an impartial historical record of violations and abuses of human rights from July 1994 to January 2017, in order to

-(i) promote healing and reconciliation,

(ii) respond to the needs of the victims,

(iii) address impunity, and

(iv) prevent a repeat of the violations and abuses suffered by making recommendations for the establishment of appropriate preventive mechanisms including institutional and legal reforms; (b) establish and make known the fate or whereabouts of disappeared victims; (c) provide victims an opportunity to relate their accounts of the violations and abuses suffered, and (d) grant reparations to victims in appropriate cases”.

During the 871 days, The Gambia and indeed the world heard from 392 witnesses, most of whom were victims of atrocities meted out to innocent civilians by the State, its agents, or individuals sponsored by both.

The witnesses appearing before the Commission also included confessed perpetrators. The testimonies heard during the 871 days of public hearings brought pain and bewilderment to the population.

They could not believe that the atrocities they heard from witnesses could occur in their country. A land of peaceful coexistence! A society imbued with a tolerance of the highest order!

They could not believe that innocent and ordinary citizens and other nationals found in the territorial jurisdiction of The Gambia, many murdered in cold blood, would-be victims of the atrocities narrated.

The Commission probing into the atrocities by President Yahya Jammeh and his cohorts achieved the desired effect of instilling fear among the Gambian population.

Nevertheless, unfortunately, it also gave them time and space to pillage the country’s resources. Among the kinds of atrocities and other human rights violations detailed by witnesses during the public hearings are the following: “Arbitrary arrests; unlawful detention; unlawful killings; torture; enforced disappearances; sexual and gender-based violence; inhuman and degrading treatment;witch-hunting; fake HIV/AIDS treatment and general and widespread abuse of public office.”

Despite such achievements, the Commission was soon mired in controversy with calls for the lead counsel of the TRRC politicized the Commission for his selfish political ambition – who was quickly linked to politics that the Commission was never investigating – or call on him to resign.

At the same time, the public hearings attracted huge media attention, and the final report was submitted to the President to be discussed in Cabinet and implemented.

The Gambian experience highlights a range of lessons and insights. As recently outlined in media reports by human rights scholars, this includes the fact that transitional justice mechanisms are not ”tools” that can be introduced in different contexts with the same effect.

Instead, their success (or failure) rests on their design, approach, and personnel – all of which are incredibly difficult to get right – but also on their evaluation and reception, and thus on their broader contexts, which commissions have little or no control over.

However, the lessons that can be drawn go beyond reception and context and extend to the inherent shortcomings of such an approach.

First, while victims appreciate a chance to speak and be heard, the majority submitted statements or memoranda or provided testimony hoping that they would be heard and that some action would be taken to redress the injustices described.

For example, after a women’s hearing, one victim explained that she was glad that she had spoken and that the Commission would “come in and help to heal, having told her story.”

The TRRC’s founders were aware of the inadequacies of speaking, so they included “justice” in the title and gave the Commission powers to recommend further investigations, prosecutions, lustration (or a ban from holding public office) reparations, and institutional and constitutional reforms.

However, on whether recommendations would be implemented, the Commission rather naively relied on the TRRC Act (2017), which stipulated that “recommendations shall be implemented.”

However, such legal provisions proved insufficient. Amidst general skepticism about the Commission’s report, although submitted to the President, it needed to be considered by the National Assembly for approval.

Moreover, documenting and acknowledging the truth requires that one hears from both victims and perpetrators. However, the latter often have little motivation and much to lose from telling the truth.

This was evident in the Gambia, where during public hearings, in some instances where we heard little that was new and not a single admission of personal responsibility or guilt.

Instead, testimonies were characterised by five discursive strands of responsibility denied: denial through a transfer of responsibility, denial through questioning of sources, denial through amnesia, denial through a reinterpretation of events, and an assertion of victimhood, and denial that events constituted wrongdoing.

However, while some witnesses denied responsibility, some did not deny that injustices had occurred.

As a result, while the hearings provided little clarity on how and why a series of reported events may have happened, they simultaneously drew attention to and recognized past injustice.

In this way, they provided a public enactment of impunity: The Gambia’s history was replete with injustice, but some perpetrators too were unwilling to shoulder any responsibility for it.

This ongoing culture of impunity points to another issue. For most victims, injustices do not belong to the past but the present and future.

The loss of a person or income, for example, often constitutes a course that now seems beyond reach – from the hardship that accompanies the loss of a wage earner to the diminished opportunities that stem from a child’s extended absence from school.

However, the past also persists in other ways, from the injustices that never ended, such as gross inequalities or corruption, to fears of repetition and experiences of new injustice.

Unfortunately, the idea that one can ”look backward to reach forwards” downplays the past’s complex ways and possible futures infringe on the present.

This is problematic since it can encourage a situation where small changes dampen demands for more substantive reform.

At the same time, it can facilitate a politicized assertion of closure that excludes those who do not buy into the absence of the past, the newness of the present, or the desirability of imagined futures and provides a resource to those who seek to present such difficult people as untrusting, unreasonable and unpatriotic.

This is not to say that truth commissions are useless and should never be considered. However, on the contrary, many views speak as better than silence.

At the same time the Commission’sCommission’s report provides a historical overview of injustice in the Gambia during former President Yahya Jammeh’sJammeh’s regime and a range of recommendations that activists and politicians use to lobby for justice and reform.

However, when introduced, truth commissions should be more aware of the importance of persuasive performances and how their initial reception and longer-term impact are shaped by broader socio-economic, political, and historical contexts.

Truth commissions also need to adopt a more complex understanding of how the past persists and possible futures infringe on the present and avoid easy assertions of closure.

Ultimately, such ambitious goals as truth, justice, reparation, and reconciliation require not Freudian “talk therapy,” although catharsis and psycho-social support are often appreciated, but an ongoing political struggle and substantive socio-economic and political change, which something like a truth commission can recommend, and sometimes contribute to, but cannot be expected to achieve.

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Recent Comments