National security has emerged as a paramount focus in the contemporary geopolitical arena, with nation-states around the world recalibrating their strategic priorities to address an increasingly complex array of threats.

In an era characterised by the proliferation of non-state actors, cyber warfare, transnational crime, and hybrid threats, the significance of resilient and adaptive national security framework cannot be overstated.

These strategies are not merely supplementary to statecraft but are the linchpin around which a state’s sovereignty, political stability, and economic viability revolve. Scholars like Barry Buzan have long emphasised that national security extends beyond the conventional defence paradigms, encompassing the protection of societal values, economic stability, and institutional integrity.

Buzan’s seminal work, “People, States, and Fear” (1991), delineates how national security functions as both a protective and a projective mechanism within the international system, enabling states to safeguard against internal disintegration while projecting power and influence externally.

In its advanced conceptualisation, national security transcends the traditional confines of military defence. It encompasses a comprehensive spectrum of state apparatuses, including law enforcement, intelligence operations, cyber defences, border control, and strategic diplomacy.

These components must operate in a synergistic manner to ensure the state’s capability to counter multifaceted threats—both external and internal—that could compromise its sovereignty and destabilise its socio-political fabric. The indicators of a robust national security architecture include a highly trained and technologically advanced military, efficient and transparent law enforcement, political cohesion, economic resilience, and a proficient foreign policy framework.

The absence or weakening of any of these elements can precipitate a cascade of vulnerabilities, potentially leading to state failure. As Frederick S. Lane argues in “Current Issues in Public Administration” (1994), the efficacy of national security is predicated on the seamless coordination of state institutions and the strategic alignment of security policies with the overarching national interest.

Unfortunately, in the Gambia, the exigency to fortify national security has been accentuated by systemic deficiencies within the administration of President Adama Barrow. Upon assuming office, President Barrow inherited a security sector marred by inefficiencies, entrenched corruption, and a notorious legacy of human rights violations perpetuated by the previous regime.

The Security Sector Reform (SSR) initiative, heralded as a cornerstone of Barrow’s strategic governance blueprint was intended to recalibrate the security forces into a professional, accountable, and modernised entity.

However, the implementation trajectory of the SSR has been beset by inertia, revealing significant flaws in the administration’s strategic approach to national security.

In essence, The Gambia’s security agencies are dysfunctional and unfit for purpose — a condition directly attributable to deficiencies in leadership and the profoundly flawed security and defence policies under President Barrow’s administration.

These policies, characterised by superficial reforms rather than substantive institutional overhauls, have left the country’s security architecture in a state of disrepair.

Security expert Mark Sedra, in his analysis of SSR in post-conflict states, argues that the failure to implement comprehensive reforms creates a security vacuum that non-state actors are quick to exploit.

The Barrow administration’s inability to effectively overhaul the security sector not only exacerbates existing vulnerabilities but also raises the spectre of state capture by entrenched elites — a dynamic extensively explored in political science literature by Francis Fukuyama in “State-Building: Governance and World Order in the 21st Century” (2004).

Sedra’s insights, particularly from his work at the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI), underscore the critical need for robust institutional frameworks that can withstand the pressures of internal power struggles and external threats.

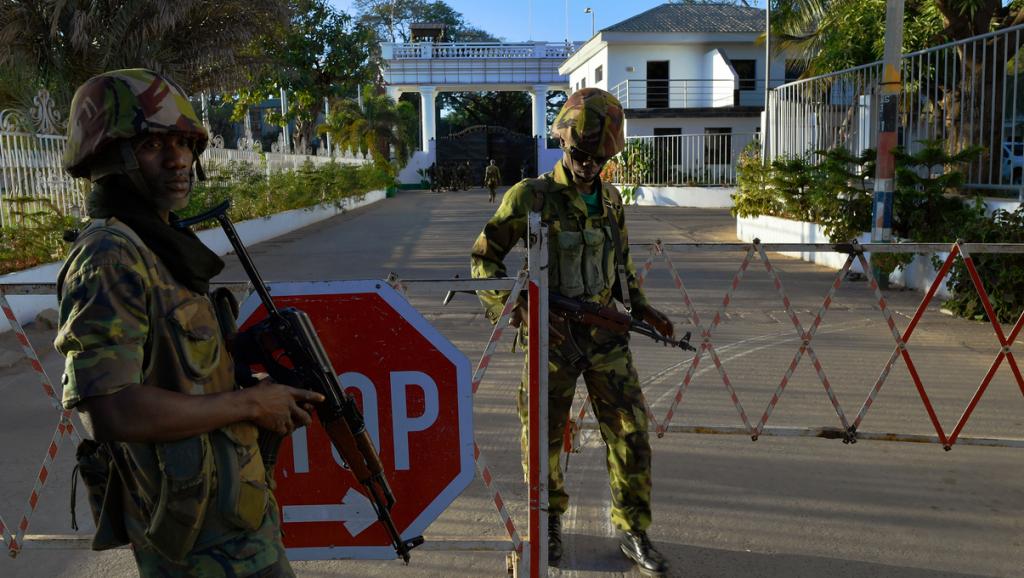

One of the most acute issues undermining The Gambia’s national security framework is its disproportionate reliance on foreign military contingents, specifically the Economic Community of West African States Mission in The Gambia (ECOMIG).

While ECOMIG’s initial deployment was instrumental in stabilising the nation during the tumultuous transition from Yahya Jammeh’s autocratic rule, the continued dependency on these external forces has underscored The Gambia’s incapacity to autonomously secure its national interests. This dependency is not only a symptom of the state’s weakened military capabilities but also a significant detriment to its sovereign integrity.

Furthermore, the recurring incursions by Senegalese forces into Gambian territory, ostensibly to pursue Casamance separatists, or even common criminals have starkly exposed the deficiencies in The Gambia’s border security and territorial sovereignty. Such extraterritorial violations, which include extrajudicial operations and the circumvention of Gambian authority, are indicative of a broader failure in the Barrow administration’s ability to assert control over its national boundaries and adhere to the principles of international law.

Kenneth Waltz’s theory of structural realism, as articulated in “Theory of International Politics” (1979), posits that reliance on foreign military forces often triggers a security dilemma, where the state’s perceived vulnerability precipitates further external interventions, thereby eroding its autonomous strategic posture.

This dynamic is further compounded by the Barrow administration’s lackluster diplomatic efforts in managing ‘win-win bilateral relations’ with Senegal—a crucial aspect of national security that demands sophisticated diplomatic insight and strategic foresight.

The theoretical frameworks advanced by Stephen Krasner in “Sovereignty: Organised Hypocrisy” (1999) are particularly relevant here, as they elucidate the complexities faced by states that struggle to maintain their sovereignty in the face of external dependencies and internal governance challenges.

With a population comparable in size to that of Texas, the Gambia is home to seven state security agencies: the Gambia Armed Forces (GAF), the Gambia Police Force (GPF), the State Intelligence Service (SIS), the Gambia Immigration Department, the Gambia Fire and Rescue Services, the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (DLEAG), and the Gambia Prison Service.

However, these agencies have proven largely dysfunctional, plagued by poor training, inadequate equipment, and rampant corruption. These systemic issues are deeply rooted in the historical legacies of the past regimes of Presidents Jawara and Jammeh, which have left a lingering impact on the structural and operational integrity of the country’s security apparatus.

Internally, The Gambia’s security apparatus remains beset by profound institutional deficiencies that have critically undermined the effectiveness of its law enforcement and intelligence agencies. Below is an in-depth analysis of each agency, accompanied by an evaluation of the service chiefs’ performance in office, as well as additional relevant insights

Gambia Armed Forces(GAF)

The Gambia Armed Forces (GAF) presents a complex profile characterised by both notable successes and conspicuous failures. On the international stage, the GAF has played a significant role in regional security, particularly through its involvement in peacekeeping missions across Africa.

This includes commendable participation in the United Nations-African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), where Gambian soldiers significantly contributed to protecting civilians, facilitating humanitarian aid, and supporting peace processes in a conflict-ridden region.

The GAF has also been an integral part of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Monitoring Group (ECOMOG), deploying troops in Liberia and Sierra Leone during their civil wars. Their role in enforcing ceasefires, supporting democratic governance, and protecting civilians from war atrocities has earned them respect and recognition.

Furthermore, the GAF contributed troops to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), aiming to stabilise the country, reduce the threat posed by terrorist groups like Al-Shabaab, and support the Somali government in establishing control over its territory.

These engagements have not only highlighted the operational competence of the GAF but have also bolstered its reputation as a committed partner in regional stability.

Despite these commendable achievements, the GAF faces severe internal challenges that compromise its current effectiveness. The military’s historical focus on regime security, particularly during the authoritarian rule of former President Yahya Jammeh, has left it inadequately prepared to address contemporary national defence challenges.

The GAF’s inability to modernise its military doctrines and equipment has resulted in a force ill-equipped to handle external threats such as cross-border incursions or potential terrorist activities.

According to Mahnken (2008), continuous adaptation and modernisation are crucial for military forces to keep pace with evolving threats. The GAF’s failure to implement these practices renders it vulnerable to external aggression and undermines its ability to project power effectively in regional security dynamics.

Another significant issue is the lack of professional military education among GAF personnel. Unlike professional militaries, where advancing through the ranks typically requires a solid foundation in military science, strategy, and leadership, many GAF officers lack formal university education or attendance at military academies.

This deficiency in education and training severely limits the GAF’s strategic leadership capabilities. During Jammeh’s regime, the culture of favouritism, rather than meritocracy, exacerbated this problem, with promotions often based on loyalty rather than competence. Consequently, the GAF’s leadership structure remains inadequately prepared for the demands of modern military command.

The absence of a coherent national defense strategy, combined with outdated military doctrines and equipment, renders the Gambia Armed Forces ineffective in their primary role of defending the nation’s sovereignty. Thomas G. Mahnken, a respected scholar in military strategy and the editor of “Technology and the American Way of War Since 1945” (2008), emphasizes the need for continuous adaptation and modernisation within military forces to keep pace with evolving threats.

The Gambia’s failure to modernise its military strategy and equipment leaves the country vulnerable to external aggression and undermines its ability to project power or influence in regional security dynamics.

The prolonged reliance on the ECOWAS Mission in The Gambia (ECOMIG) under President Adama Barrow’s administration has further sidelined the GAF from its traditional roles. This outsourcing of national security functions to ECOWIG has undermined the morale of Gambian soldiers, eroded public confidence in the GAF’s capability to defend the country independently, and challenged the recruitment and training of new personnel.

While ECOMIG troops have performed admirably, their presence cannot substitute for a competent, homegrown security force. This reliance on foreign forces is a tacit admission of failure and highlights the inadequacy of local security institutions.

It is deeply ironic that the GAF, lauded for their role in peacekeeping missions across conflict-ridden regions like Sudan and Liberia, remain incapable of securing their own borders without the assistance of foreign troops. This contradiction evokes the dark humour of a strategic playbook where a nation, adept at projecting strength internationally, cannot muster the capability to address its internal security challenges.

Despite their impressive international credentials, the GAF’s continued reliance on external forces underscores a sobering reality: a military force celebrated globally yet struggling with the most basic tenets of national defence.

By Arfang Madi Sillah, Washington DC

To be continued.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institutions or organizations. The author takes full responsibility for the opinions and analysis presented herein. The author holds several academic degrees, including an undergraduate degree in English literature and literary theory.

Read Part One of this article here.

Recent Comments