The landmark case of Mayor Pa Sallah Jeng versus The Minister of Local Government and Lands revisited.

All that has been said about the nature and extent of formal democratic governance in the First Republic is generally identical with and applicable to the Second Republic. The 1970 and 1997 Constitution recognized the doctrine of separation of powers and guaranteed the rule of law and the independence of the judiciary.

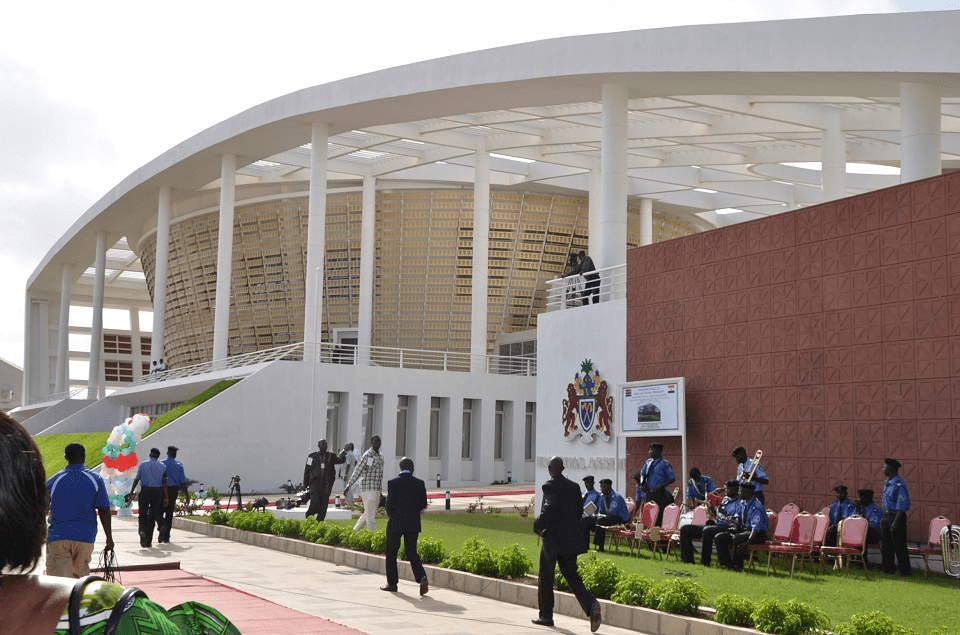

Article 42 of the 1997 Constitution vested the executive powers of The Gambia in the President, while article 56 vested the legislative powers of the country in the National Assembly, and Part I of chapter 8 entrusted the judicial power of the republic to the courts of the land.

The Gambia had during this period maintained many legislative enactments passed by the colonial administration and enacted many other laws to support the Constitution in the governance process. All this is true in theory, but in practice the chief executive officer of the nation, like many other African presidents, during this period usurped all other arms of government and became the most powerful man in the country.

The essence and concept of parliamentary democracy may not work in the Gambia, for the simple reason, we have got a political and social structure which is totally incompatible with the principle of devolution, representative and parliamentary democracy. I know of a political sage for decades advocating that the Local Government Act be reformed to give Mayors and Councillors the power of oversight, autonomy to legislate the affairs of their municipal councils over the minister of Local government. The Minister of Local Government, who is an unelected official is vested with broad overarching powers has the audacity to veto any decisions and policies of elected Mayors and Councillors. The Minister also has the powers and audacity to remove an elected Mayor in office.

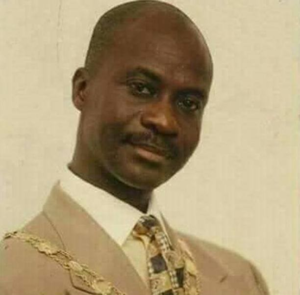

Mayor Pa Sallah Jeng v The Minister of Local Government and Lands is a classic case of the Gambia’s democracy that is incompatible with the principle of devolution and representative democracy.

For example, the Minister of Local Government and Lands with the support of the executive connived to remove the Banjul Mayor. How can a minister pressed charges and suspends (the then) Mayor of Banjul, Pa Sallah Jeng and charged him with six counts of Economic Crimes contrary to section 5 (f) of the Economic Crimes (Specified Offences) Decree 1994; abuse of office by a public officer contrary to section 90 of the criminal code and economic crime contrary to section 5 (e) of the Economic Crimes (Specified Offence) Decree of 1994.

According “to the particulars of the offence Mr. Jeng as Mayor of Banjul City Council between the months of January and February 2005, in breach of section 45 of the Gambia Public Procurement Act and Section 12 of The Gambia Public Procurement Regulations intentionally singly sourced and directed the purchase of a second hand towing ambulance for a sum of D340,000 to the detriment of the economy of The Gambia”.

In July 2006, the High Court in Banjul invalidated an executive order issued by the Minister for Local Government and Lands dismissing the Mayor of Banjul, Pa-Sallah Jeng. The High Court ordered that the Mayor be reinstated with immediate effect. In all, the Gambian judiciary had to take a bold stand to assert its authority and independence to uphold the principles of justice, equity, the rule of law and fair play in the governance process. However, the cost of fighting to maintain institutional autonomy and independence in The Gambia has been quite significant.

For years, that political sage had argued about the contradiction and coexistence of a Mayor who is elected by the people and a State Minister appointed by the president according to the Local Government Act undermine the concept and principle of devolution and parliamentary democracy.

He argued that the Gambia have inherited the idea that the Mayor must have no power at all, that he must be a rubber stamp. If a minister of Local Govt, however scoundrel he may be… puts up a proposal before the Mayor, he must approve it. This is the kind of conception about devolution and democracy which we have developed in this country.

While it is apparent that devolution has been designed to transfer decision-making and resources from the centre to the grassroots, it is indisputable that Council should focus mainly on policy formulation and largely dwell on policy implementation. The government must entrench these very attributes in the workings, style of Municipal Councils even as it navigates politically explosive issues.

From 1997 onwards, the Gambia has been governed by a written Constitution, defined by section 4 as being the supreme law of the land to which all laws, government policies, executive orders, decisions and all other governance activities should conform. The remaining democratic values of the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms, observance of the rule of law, the independence of the judiciary, multiple political party participation in the political process of the country, free and fair periodic elections, the doctrine of separation of powers, and transparent and accountable government, are guaranteed by the 1997 Constitution of the Second Republic of The Gambia only on paper and not in reality.

This article was first published on 15 April 2018

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Recent Comments