Arfang Madi Sillah, a Washington D.C.-based Gambian scholar and commentator, has written a compelling and thought-provoking book titled The Curtain Falls on the Press and Presidency Relationship—Barrow Goes Berserk.

Known for his incisive political analysis and deep understanding of Gambian affairs, Sillah examines the fraught relationship between the press and the presidency in The Gambia, particularly under President Adama Barrow’s administration.

Below is an abridged version of the book.

Chapter 2: The Fall of Mighty Tabloid

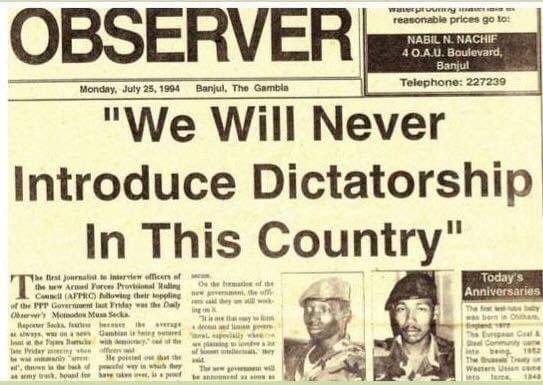

For 25 years, The Daily Observer stood resilient, weathering storms that would have sunk even the mightiest newspapers in places like imperial Russia, where the Tsarist regime shut down publications with brutal regularity, or in revolutionary France, where pamphleteers were imprisoned for daring to criticise the state.

Much like those in the early days of Fleet Street or the clandestine newspapers of Weimar Germany, The Daily Observer fought on, publishing in an environment where the very act of reporting could invite retribution.

Its pages, like the defiant underground presses of Franco’s Spain or Apartheid-era South Africa, held within them the pulse of resistance, a truth too bold to be silenced. And yet, despite the constant threat of state retaliation, the paper persisted, standing as a symbol of defiance and a tribute to the resilience of the press.

For the journalists who worked at The Daily Observer, especially during the darkest years of Yahya Jammeh’s brutal dictatorship, the battle for free speech was not just a metaphor—it was a life-and-death struggle. Editors and reporters were not merely censored—they were pursued, arrested, tortured, and deported with the ruthless efficiency of a state determined to suppress every dissenting voice. Jammeh, much like Stalin’s NKVD or Pinochet’s secret police, led a crusade against the press, rounding up foreign journalists like the illustrious Sule Musa, deporting them as if they were dangerous revolutionaries.

And when expelling foreign correspondents failed to quench his thirst for control, Jammeh turned his sights on Gambian-born journalists.

Baba Galleh Jallow, a son of Farafenni and once the head boy at Gambia High School, narrowly escaped deportation after being mistaken for a foreigner in a farcical episode of state paranoia. It was the absurdity of despotism at its finest—where even your nationality could be questioned by the regime in its frenzy to control the narrative.

Inside The Observer’s newsroom, the atmosphere was charged with the tension of a war zone, where the simple act of reporting became a subversive strike against the iron fist of the state. Journalists operated under the constant threat of raids, arrests, and state-sponsored intimidation.

Yet, like the muckrakers of early 20th-Century America or the bold writers of Samizdat publications in Soviet Russia, the journalists at The Daily Observer remained unbowed. They had seen the worst the regime could throw at them, from secret police interrogations to the shuttering of their offices.

So, when Barrow’s administration took over, many seasoned reporters thought it was just another round of political theatre—a new regime flexing its muscles. After all, they had outlasted Jammeh—what could Barrow’s government possibly do that they hadn’t already survived?

But Barrow’s tactics were subtler, less overt, but no less effective. This wasn’t the era of secret police and midnight knocks on the door. Instead, Barrow’s administration wielded the weapons of financial suffocation and bureaucratic strangulation with the precision of a seasoned autocrat. The assault wasn’t about arrests or disappearances—it was about tax bills, regulatory fines, and legal notices.

What Jammeh couldn’t achieve through force, Barrow sought to accomplish through paperwork and financial ruin. Like the quietly insidious legal warfare waged by Nixon’s administration against the Washington Post during the Watergate scandal, Barrow’s government used bureaucracy to strangle The Observer out of existence without ever firing a shot.

For the battle-worn journalists, this was a new kind of war. It wasn’t fought in the streets or with megaphones—it was a war waged behind the closed doors of administrative offices, where ledgers and tax codes replaced handcuffs and riot police.

So, what had started as a hopeful new dawn for democracy under Barrow quickly morphed into another chapter of press repression, this time cloaked in the polite language of fiscal responsibility and legalistic procedure. The fight for The Daily Observer was far from over, but the battlefield had changed, and the enemy now wore the face of bureaucratic efficiency rather than military dictatorship.

The fall of The Daily Observer was a watershed moment in Gambian media, marking a profound shift in the dynamics of the press. Founded in 1992 by the esteemed Liberian journalist Kenneth Best, the paper had long stood as a torchlight of fearless journalism, exposing corruption and speaking truth to power with the kind of boldness that only the truly independent can afford.

But the tide began to turn in 1999 when Kenneth Best sold The Observer to Amadou Samba, a businessman firmly ensconced in Jammeh’s inner circle. Much like Hearst’s purchase of major newspapers in the early 20th Century, this wasn’t merely a business deal—it was the beginning of the end for the paper’s editorial independence.

The shadow of Jammeh quickly spread over the once-independent Observer, transforming it from a vibrant, critical voice into little more than a mouthpiece for the regime. Journalists who had built their reputations on integrity and courage—people like Baba Galleh Jallow, Demba Ali Jawo, Alieu Badara Sowe and Pa Nderry Mbai—were swiftly dismissed in a purge that sent shockwaves through the media landscape.

The newsroom that had once been a bastion of press freedom became a state-controlled megaphone, with every word scrutinised and sanitised by the regime’s ever-watchful eye. Like the great purges of critical voices in Weimar Germany, The Observer’s transformation was swift and devastating.

Despite its fall from grace, The Daily Observer remained a major player in Gambian media. But when Yahya Jammeh was finally ousted, the paper’s fate was sealed, much like a Greek tragedy where the hero’s downfall is sealed by the loss of divine favour. No longer shielded by the regime it had once supported, The Observer became vulnerable to the same tactics it had helped enforce.

In June 2017, the Gambia Revenue Authority closed the paper’s doors, citing an unpaid tax bill of 17 million dalasis. But few believed the official story. Much like the closure of The Times under Margaret Thatcher’s government during the Wapping dispute, this was about power, not money. The demand for an immediate 30% settlement of the bill was financial warfare, designed to ensure the paper’s demise.

On June 14, 2017, The Daily Observer was shuttered, its offices sealed, and hundreds of employees left without jobs. The management’s offer to settle the debt over twenty years was rejected out of hand, a clear sign that the closure had nothing to do with taxes and everything to do with silencing a potential threat to the new political order. The tactics were new, but the outcome was the same—The Observer, once the titan of Gambian journalism, was no more.

What was perhaps most unsettling was the silence from the rest of the media. The Gambian Press Union issued a mild statement, but there was no collective outcry, no show of solidarity. Some media outlets even saw The Observer’s demise as an opportunity to expand their own influence—a short-sighted move that ignored the broader implications of the government’s actions. Like the fracturing of Fleet Street when The News of the World fell in scandal, the Gambian media failed to see that the fall of one paper weakened the entire ecosystem.

The ripple effect was immediate. Journalists across the country took note: if The Daily Observer could fall, none of them were safe. Self-censorship spread like wildfire, as media outlets already dependent on government advertising revenue grew even more cautious.

Where once bold reporting had been the hallmark of Gambian journalism, caution and timidity now ruled the day. The closure of The Observer was a stark reminder that even in a post-Jammeh Gambia, press freedom was fragile, and the government’s grip on the media was far from loosened.

More troubling was how the paper was not only betrayed by its sister newspapers, but by its own sons and daughters—the journalists who once worked there, built their careers, and established their fortunes. These journalists, who owed much of their success to the crucible that was The Daily Observer, turned a blind eye and maintained tight lips as the mighty paper was brought to its knees. It was as if the closure of this media giant was an act of divine will, when in fact, it was the result of human neglect.

The closure of The Daily Observer wasn’t just the end of a newspaper—it was the beginning of a new era of media monopolisation. Fewer outlets now controlled the narrative, and the diversity of thought that had once defined the press began to shrink.

Other publications may have celebrated their increased market share, but they failed to see the bigger picture: the elimination of The Observer weakened the entire press landscape. The media became ripe for manipulation, as the remaining outlets faced the same financial and political pressures that had led to The Observer’s demise.

Long before the Gambian government even entertained the thought of establishing a school of journalism, The Daily Observer had already cemented its place as the veritable cathedral of Gambian journalism, functioning as a de facto academy for journalists. It wasn’t merely a newsroom—it was a classroom, shaping the next generation of journalists, writers, and scholars with hands-on experience and mentorship.

The newsroom, helmed by seasoned editors who doubled as mentors, welcomed not only trained journalists but also aspiring writers—students with a passion for the written word. It was a sanctuary for the curious, the bold, and the restless—a place where the spark of inquiry was nurtured and transformed into the fire of journalism.

Young talents like Baboucarr Ann, Rohey Samba, Bamba Khan, Bankole Thompson, Sheriff Bojang Jr., and Simon Peter Mendy all started writing for The Observer while they were still in high school or middle school.

And unlike today’s internship models, which often exploit young talent for free, The Observer paid its contributors handsomely, recognising that good journalism deserves good compensation. The paper, like the great publications of Victorian England, understood that fostering talent was not only about opportunity but also about fairness.

This paper was the bedrock upon which many of today’s prominent media figures built their careers. Momodou Musa Touray, now the publisher of Gambiana; Sheriff Bojang, the publisher of The Standard; Assan Sallah, the publisher of LamToro News; and Bankole Thompson, the publisher of The PuLSE Institute, a Detroit-based, independent non-partisan think tank—all of them are products of The Daily Observer.

Today, these men now hold the levers of power in Gambian and international media, continuing the tradition of journalism they honed at The Observer. Their rise to prominence in the media landscape speaks volumes about the training and opportunities The Observer provided to young journalists, offering them a platform from which they could grow into industry leaders.

Beyond the media realm, the impact of The Daily Observer has reverberated across many sectors of Gambian society. Countless former staffers of the paper are now making waves in a wide range of fields, from politics to academia, law, and public service. Take, for example, Yankuba Darboe, the current chairman of the Brikama Area Council, whose time at The Observer sharpened his skills in public communication and administration. His rise in local government is a reflection of the far-reaching influence the paper had in shaping minds capable of leading and influencing communities.

In the legal field, we have Lawyer Alhagie Abdoulie Fatty, another former Observer journalist, who has carved out a significant presence in Gambian law, representing high-profile cases and advocating for justice. Fatty’s journey from the newsroom to the courtroom exemplifies how the skills of critical thinking, research, and analysis honed at The Observer can translate into effective legal advocacy and leadership. His transition from writing headlines to defending the downtrodden in courtrooms recalls the transformation of the ancient Greek orators—think Demosthenes—whose rhetorical prowess and commitment to justice influenced the course of history.

Academia, too, is home to Observer alumni.

Dr. Ebrima Ceesay, now a respected professor at the University of Birmingham, is another product of the paper’s rigorous journalistic environment. His scholarly contributions and his work in educating the next generation of thinkers and leaders can be traced back to the foundations he built during his time at The Observer.

His colleague, Dr. Baba Galleh Jallow, has also made his mark, contributing to the intellectual landscape both in The Gambia and abroad. Much like the ancient Athenian academies, The Observer was a modern-day Agora, where debates, ideas, and critical thought flourished.

One cannot help but draw parallels with Fleet Street in its heyday, when it wasn’t just a hub for journalism but a breeding ground for intellectuals, reformers, and future statesmen. Just as figures like Charles Dickens, who began as a Fleet Street journalist, went on to shape British literary and social thought, so too have the graduates of The Daily Observer moved beyond the confines of journalism to influence law, politics, and scholarship. The Observer’s newsroom was akin to a crucible of talent, where raw potential was refined into the very leaders shaping modern-day Gambia.

The list of distinguished alumni does not stop there. The Daily Observer nurtured a wealth of talent that has dispersed into various sectors, with former staffers contributing to business, education, and civil society. The paper was not just a media institution; it was a training ground for excellence, instilling in its staff a sense of responsibility, critical thinking, and a commitment to truth and service that transcended journalism.

As the Greek philosopher Heraclitus once mused, “Character is destiny”—the Observer forged character in its staff, and their collective destinies now play out on national and international stages.

And yet, despite their successes, the closure of The Observer passed with little more than muted murmurs.

These alumni of The Observer, many of whom now wield significant influence, could have banded together to rally for its survival, to challenge the government’s decision, or at least ensure the dignity of the paper’s closure. But there was no grand defence mounted, no significant effort to fight back.

To compound matters, while The Daily Observer was shuttered and its staff left unpaid, the government’s actions were cloaked in a veneer of legality. The argument was that the paper owed taxes—but the amount cited was not enough to justify the indefinite grounding of such a vital media institution.

Activists such as Madi Jobarteh, who are now vocal about the ongoing standoff between President Barrow and The Voice, should be reminded that The Observer deserved no less of a defence than The Voice does today. In fact, The Observer deserved it more, as they were victims in a war not of their making, while some of The Voice’s troubles are self-inflicted.

The failure to defend The Observer was not just a failure of the media; it was a failure of Gambian society to stand up for one of its key institutions. The very paper that trained so many journalists, built so many careers, and became a voice for the people, was left to die, not because it deserved to, but because those who could have fought for it chose not to. It was a betrayal of the highest order, a reminder that in the cutthroat world of media, even the mightiest can fall if those they helped elevate turn their backs at the crucial moment.

In the final analysis, the closure of The Daily Observer was more than just a blow to the press—it was a blow to Gambian democracy itself. Without a free and independent press, corruption thrives, power goes unchecked, and the people are left voiceless in the face of injustice.

Then came a twist of irony so bitter that it left many shaking their heads. Not long after the closure of The Daily Observer, The Standard, one of the country’s leading newspapers, awarded its prestigious ‘Man of the Year’ title to the very figure whose institution had overseen the shutdown of The Daily Observer.

This decision stunned the media community, as the award went to the head of the Gambia Revenue Authority (GRA), the very agency responsible for enforcing the closure. The Standard, in its celebratory piece, praised the awardee for his dedication to national development and commitment to fiscal responsibility. Nowhere in the glowing accolades was there any mention of the hundreds of jobs lost or the damage done to press freedom through the closure of the country’s largest newspaper.

For many, the decision to award such an honour to someone so closely linked to the suppression of The Daily Observer felt like a betrayal of journalistic principles. It was a stark reminder that the media was not immune to the same political and economic pressures that had long shaped other sectors.

The award ceremony was held with pomp and circumstance, attended by the country’s political and business elite. Speeches were made, and toasts were raised, all while the ghost of The Daily Observer loomed large over the proceedings. The very institution that had silenced a major voice in Gambian journalism was being celebrated, while those left jobless and voiceless by the paper’s closure watched in stunned disbelief.

Simply put, The Standard newspaper’s baffling choice to crown Yankuba Darboe, the Commissioner General of the GRA, with the highest accolade a newspaper could offer, was the height of absurdity. Here was a man presiding over an organisation that had become synonymous with corruption and bureaucratic buffoonery. What on earth were the criteria? Was it the efficiency of his spin machine or the depth of his advertising budget?

How many dalasis did the GRA pour into The Standard’s coffers to secure this honour? The situation was eerily reminiscent of the practices described by David Simon in Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, where local politicians bought favourable coverage from cash-strapped newspapers.

A similar case can be seen in post-Soviet Russia, where media moguls close to the Kremlin have been known to orchestrate awards and accolades to government officials in exchange for favourable coverage, thereby eroding the very principles of independent journalism.

The absurdity of the situation wasn’t lost on the public or the journalistic community. It revealed the widening gap between the ideals of the press and the reality of its operations in The Gambia. The awarding of a ‘Man of the Year’ title to someone so entangled with the destruction of The Daily Observer was not just an insult to the profession, but a sobering acknowledgment that even the press could be bought and sold, its moral compass thrown off course by political and financial expediency.

This event left a deep stain on Gambian journalism, raising uncomfortable questions about the role of the media in a post-Jammeh Gambia, and whether it was truly free, or simply reshaped to serve a new set of masters. The case is reminiscent of Mexico’s Manuel Buendía case, where investigative journalists were killed or silenced, and the government honoured figures of authority who played a role in the suppression of press freedom. Awards were used as tools to cleanse reputations, leaving the public disillusioned and the journalistic community demoralised.

Ultimately, this recognition by The Standard symbolized a disturbing normalisation of state influence over the press. Rather than standing as an institution that held power to account, the media seemed increasingly complicit in bolstering those very forces that sought to silence it. It wasn’t just the closure of The Daily Observer that was troubling—it was the growing sense that the entire media landscape had become a mere extension of the same political machinery that once crushed dissent.

This moment set a dangerous precedent, one in which the press, once the guardian of democracy, was slowly being turned into its own gravedigger. As seen in Turkey under President Erdoğan, where once-thriving independent media outlets were systematically shut down or co-opted into state-run propaganda machines, the parallels were stark.

The Gambia now risks heading down the same path, where press freedom exists only in name, while the media quietly succumbs to political influence and economic pressures. The once-vibrant journalistic landscape is in peril, as the grip of power tightens around the throat of free expression.

To be continued.

By Arfang Madi Sillah

Washington DC

Read Part One of the book here.

Recent Comments