Despite Adama Barrow’s comfortable win in December’s presidential elections, his party failed to clinch a convincing majority in recent National Assembly polls.

Without the deciding vote, it will be difficult for Barrow to govern and ensure that long-overdue constitutional reforms work in his favour.

In the December poll, the president garnered 53% of the vote, with his closest contender Ousainou Darboe managing just 27.7%.

Barrow’s National People’s Party (NPP) failed to replicate these gains in the National Assembly elections held in April this year.

The NPP fell short of securing the majority, with a final tally of 24 seats (out of 58), including the president’s five nominated legislators.

The party’s lacklustre performance follows a series of missteps in Barrow’s first term. He enters his second term amid popular discontent over Gambia’s struggling economy, heightened insecurity and a stalled reform process.

This is in sharp contrast to the optimism that characterised the start of Barrow’s presidency when he ended Yahya Jammeh’s 22-year autocratic rule. Barrow came to power in 2017 after a campaign by the United Democratic Party (UDP) under the Coalition 2016 banner (together with six other parties).

Barrow made lofty promises in his first days in office, adopting an ambitious National Development Plan that aimed to “deliver good governance and accountability, social cohesion, and national reconciliation and a revitalised and transformed economy for the wellbeing of all Gambians.”

Unfortunately, political tensions soon arose, driven by a power struggle between the president and the UDP’s leader Darboe.

Barrow’s decision to serve a full five-year term after committing to only three years widened the rift between him and the UDP.

He sacked several high-level opposition figures from government and removed Darboe as vice-president as his relationship with his former coalition partners deteriorated.

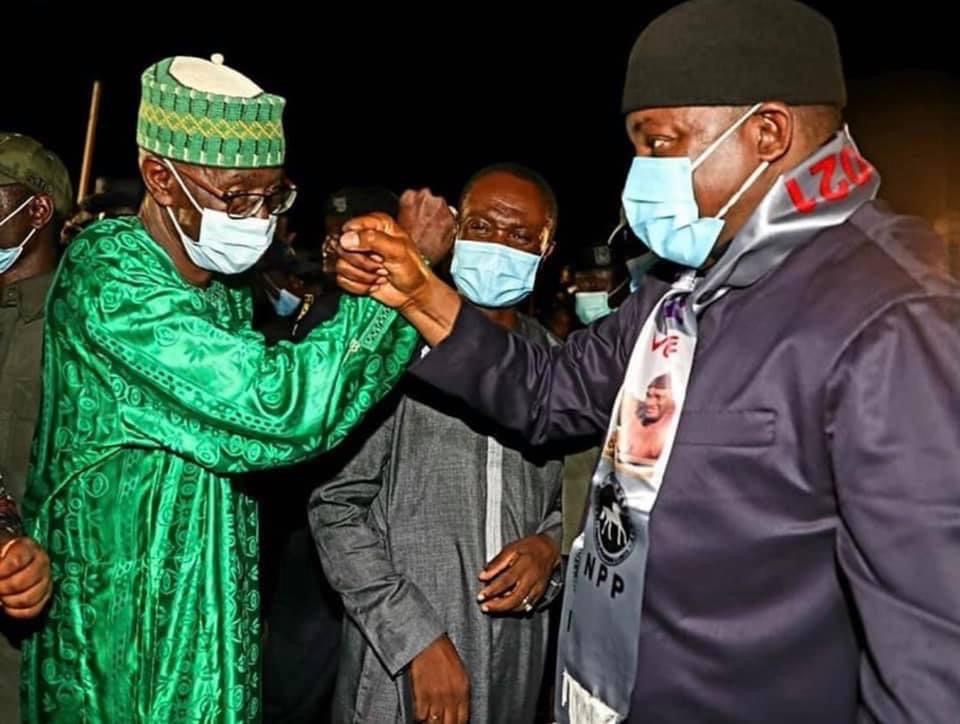

In 2020 Barrow officially ended his alliance with the UDP when he formed the NPP. Since its launch, the NPP has faced an uphill battle to establish itself within Gambia’s political space.

Apart from steep competition from the UDP, Barrow and his party also had to contend with a serious challenge from the Three Years Jotna movement.

The movement was formed to oppose Barrow’s decision to serve a full five years after promising just three as president. Following a wave of protest, the grouping was banned in 2020.

Faced with increasing political pressure, Barrow made the controversial move to align with Jammeh’s party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC).

This raised ire from survivors of Jammeh-era human rights violations who feared that the president’s new allies would impede the prosecution of perpetrators.

The Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission’s final report submitted on 24 December seemed to have laid the victims’ concerns to rest.

The commission has recommended criminal trials for the accused, including Jammeh, for crimes ranging from murder to sexual assault.

Barrow urged the public to be patient as a white paper is prepared on implementing the commission’s proposals.

But questions remain about the president’s commitment to the process, especially in light of his alliance with the APRC.

The outcry against the NPP-APRC coalition was one of the many signs that Barrow’s party would struggle to secure support.

The NPP’s recent electoral performance confirms that citizens remain sceptical of the party.

Without a convincing majority in the National Assembly, the president is five seats short of the votes he needs for a quorum to pass ordinary bills.

He also lacks the three-quarters majority required to make constitutional amendments.

Party support in the National Assembly will be critical to Barrow’s handling of stalled constitutional reform that has remained unresolved since his first term.

Gambia’s constitutional review process was halted in September 2020 when the National Assembly rejected the draft constitution that would have replaced the 1997 constitution.

Notably, the draft contained a new clause limiting a president to two terms, whereas Barrow can run for another term under the current constitution.

The existing Jammeh-era constitution is however deeply controversial, which leaves Barrow with two options — revise the rejected draft or amend the current constitution to add new provisions.

Either one of these processes would be cumbersome and require three-quarters of National Assembly votes followed by a national referendum.

If a new constitution is adopted or the current one amended, Barrow may try to ensure that the term limits are not applied retrospectively, and executive powers are not severely curtailed.

Barrow has promised Gambia a new constitution with term limits but remains tight-lipped on whether he would stand for another term.

Even if Barrow can get the APRC and independent legislators to back him, he would still need at least one vote from the UDP to get the required tally.

This suggests he is unlikely to garner the support to ensure constitutional provisions in his favour.

So the president’s second term will be a delicate balancing act between maintaining his political legitimacy and consolidating his power.

He faces the predicament of continuing his tenure under a controversial constitution or reforming the constitution and, in the process running the risk of limiting his executive power.

By Chido Mutangadura,

Consultant, Institute for Security Studies (ISS) Pretoria.

First published by ISS Today.

This ISS Today is published as part of the Training for Peace Programme (TfP), funded by Norway’s government.

Recent Comments