It is seldom that a local government institution in The Gambia intervenes meaningfully in the domain of higher education. For decades, councils have functioned as administrative satellites of the Ministry of Lands and Local Government: poorly funded, technically disempowered, and conceptually divorced from the developmental imagination.

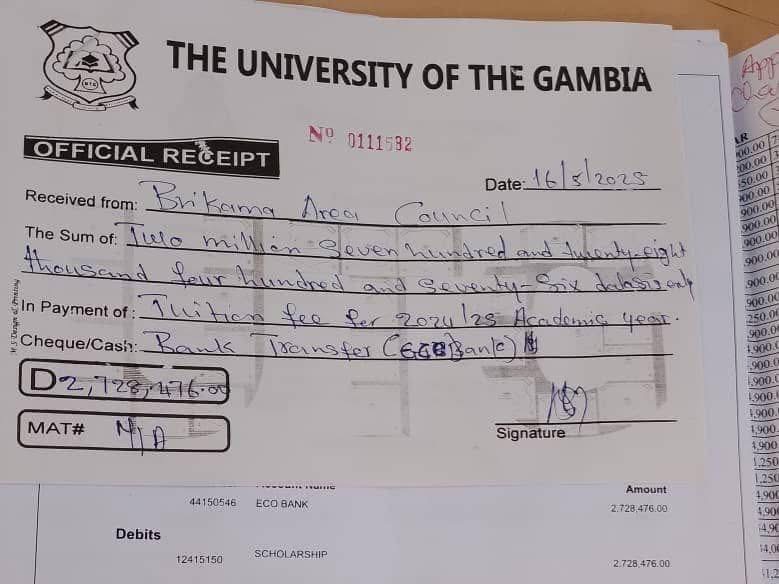

The recent announcement by the Brikama Area Council, committing over D2.7 million in tuition assistance for seventy-five students at the University of The Gambia, marks a quiet rupture with that legacy.

More importantly, it raises critical questions about the structural relationships between local government, social mobility, and educational justice in a state still grappling with the consequences of centralisation.

This development is not accidental. It is the product of deliberate leadership by Chairman Yankuba Darboe, a trained lawyer and public administrator whose assumption of the chairmanship of Brikama Area Council is, in itself, a significant institutional departure.

Until now, no Gambian intellectual with advanced academic training had entered local government service through electoral means. His candidacy and subsequent election were, for some of us, grounds for cautious optimism not because of partisan sympathy, but because it signaled the arrival of a new kind of leadership at the subnational level—one that speaks the language of governance rather than the dialect of populist improvisation.

What Chairman Darboe has done with this policy intervention is to translate the abstract principles of decentralization into something tangible. He has demonstrated that local councils need not remain ceremonial entities dependent on central transfers or externally driven development blueprints.

Instead, they can act within the bounds of their legal and fiscal capacity to address gaps that national policy has consistently failed to fill. By directing council funds toward university tuition, he has disrupted the long-standing assumption that higher education is the exclusive concern of the central state.

This raises important theoretical and practical implications. From a governance perspective, the BAC initiative constitutes a textbook case of functional decentralisation, where the local government identifies a domain of social vulnerability and intervenes without waiting for permission.

It also affirms the notion that education policy need not be monopolised by national ministries whose priorities often oscillate with the political winds. What we witness here is a council positioning itself not simply as a service provider, but as a developmental actor.

From a public policy standpoint, the implications are equally profound. The seventy-five students selected are not abstractions. They represent real families and real aspirations—and had this funding not materialised, real despair. Many would have suspended or abandoned their studies altogether.

By intervening, the Council has not merely sponsored tuition. It has preserved intellectual potential, protected household investments in education, and contributed modestly but meaningfully to national human capital development.

It is worth asking why this model has not been pursued elsewhere. The answer lies partly in the absence of intellectual leadership in many councils, and partly in the structural infantilisation of local governments by the central state.

Councils have been trained to defer. Budgets are allocated downward, rarely generated internally. National politicians, especially in the executive branch, have been reluctant to empower councils with the fiscal autonomy or policy latitude required to think beyond potholes and waste bins.

Chairman Darboe’s intervention challenges that architecture. He is not just managing a council. He is exercising a theory of change. And in doing so, he reminds us of what happens when educated minds enter spaces previously reserved for the politically connected or administratively indifferent.

The central government ought not only to acknowledge this initiative, but to reflect on its own inadequacies. Why has the Ministry of Higher Education been unable to develop a robust tuition subsidy scheme for the neediest students?

Why must undergraduates rely on Gambians in the diaspora to cover basic tuition? And why, in a state that claims to champion youth empowerment, are the nation’s brightest routinely priced out of its only public university?

The Brikama model is not a substitute for national policy. But it is a provocation. It dares other councils to think beyond the mundane. It challenges the central government to reconsider the distributive logic of the national budget. And it offers scholars and practitioners a concrete example of how decentralization, when animated by competence, can serve as a tool for educational inclusion.

What Chairman Darboe has done is not revolutionary. But in the context of Gambian governance, it is rare, courageous, and instructive. It deserves more than applause. It deserves replication.

By Kebba Jammeh

Recent Comments