In the theatre of war, there is a fine line between strategic imitation and blatant mimicry — a distinction famously dissected by the great strategist Sun Tzu in The Art of War. He warned of the perils of imitation without innovation, of copying tactics without understanding their true intent.

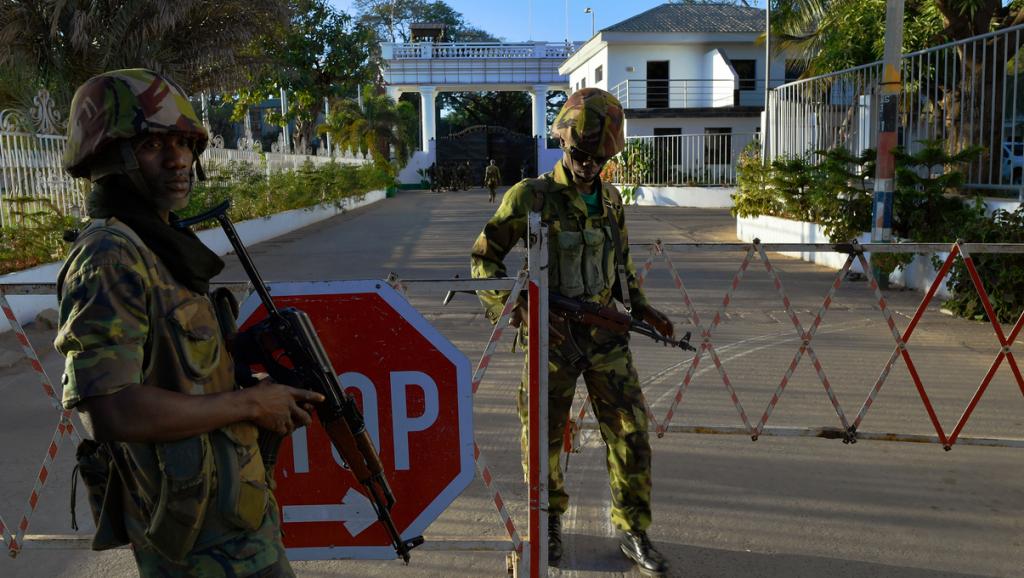

It is a lesson the Gambia Armed Forces (GAF) would do well to heed, for they have turned the ancient art of psychological operations (PsyOps) into a modern farce — an exercise in self-delusion rather than strategic deception.

The GAF’s recent manoeuvres resemble less a coherent military strategy and more a grotesque parody of PsyOps — an opera buffa where the punchline is, regrettably, the nation’s own security.

PsyOps, when wielded correctly, is a potent weapon in a military’s arsenal, capable of shaping the battlefield as surely as any bomb or bullet — offering a twofold utility as both shield and sword. As a shield, it can cloak manoeuvres in a veil of secrecy, deflecting enemy scrutiny and managing the delicate balance of public perception.

As a sword, it cuts deep into the enemy’s psyche, sowing seeds of doubt and despair, weakening resolve. However, like any double-edged blade, PsyOps requires precision; its misuse can cause it to backfire. Hence, the peril of entangling PsyOps with routine military operations is profound.

When deception and reality blur, the line between strategic gain and catastrophic collapse becomes perilously thin. Yet, rather than mastering this art and leveraging its full potential, the GAF has reduced it to a mere imitation game, turning PsyOps into a dark alchemy rather than a disciplined strategy.

Consider, if you will, the dubious saga of Gen. Bora Colley, a tale hastily spun into a supposed military triumph. The GAF’s proclamations of his “arrest” or “surrender” ring hollow, even to the most credulous of audiences. Given his infamy and notoriety, one might expect Gen. Colley’s arrest to resemble a swift, decisive operation — a blitz executed with the pinpoint precision of a commando raid.

A surrender, by contrast, would imply a dramatic crescendo to a relentless pursuit, where the adversary, exhausted and cornered, has no choice but to capitulate. What unfolded with Gen. Colley, however, was neither; it resembled a poorly directed production, more fitting for the stage of a provincial playhouse than the annals of military history, complete with overblown claims and a storyline riddled with plot holes that would embarrass even the most amateur of scriptwriters.

To the untrained eye, this might seem like just another typical day in the topsy-turvy world of West African military affairs. But for those of us seasoned in the art of military analysis, accustomed to reading between the lines of battlefield communiqués and parsing the true meaning behind the coded language of conflict, this episode reeks not of competence but of sheer desperation.

The annals of warfare are replete with instances where psychological operations were executed with precision to change the course of events — from the deceptive brilliance of Operation Fortitude in World War II, which convinced the Germans that the D-Day invasion would land elsewhere, to the calculated propaganda of the Tet Offensive, which sapped American public support for the Vietnam War despite a tactical victory.

In such contexts, PsyOps were wielded like a scalpel — precisely, strategically, and with devastating effect. Here, however, the Gambian Armed Forces have wielded them more like a sledgehammer — bluntly and ineffectively, aimed not at an enemy force but at their own citizenry.

A closer look at the slapdash PR campaign surrounding Gen. Colley’s supposed apprehension reveals a force that is clearly out of its depth. A hastily scribbled press release, disseminated with unwarranted urgency, does not reflect a carefully coordinated information campaign but rather a panicked scramble for damage control.

The language employed bore no resemblance to the stern, disciplined tones of a military operation in control of its narrative. Instead, it read like the frantic dispatches of a force caught off guard, desperately trying to regain its footing in a rapidly deteriorating situation.

This is not the first time the Gambian military has found itself the laughingstock of its own propaganda. We need only look to the British campaign during the Malayan Emergency for a stark contrast.

There, psychological operations were employed with surgical precision: leaflets dropped from aircraft carrying messages designed to erode guerrilla morale, loudspeakers broadcasting surrender calls across enemy lines, carefully crafted narratives that slowly but surely turned the tide against insurgent forces.

The Gambia’s effort, by comparison, is laughable — akin to deploying toy soldiers in a real battle, with messages scribbled in crayon and delivered via tin cans on strings. This is not the work of a military force; it is the work of an amateur dramatics society, performing for an audience that deserves much better.

This distortion of reality brings to mind the notorious case of the U.S. intelligence community’s misreporting of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in Iraq, which led to a costly and catastrophic invasion.

In 2003, the U.S. intelligence community, driven by a mix of faulty assessments, confirmation bias, and political pressure, produced a now-infamous report that falsely claimed Iraq possessed WMDs.

This intelligence, presented as an undeniable truth, led policymakers and the public alike down a path to war — a costly, bloody conflict that continues to reverberate throughout the region and beyond.

The intelligence was not only misleading; it was catastrophically convincing, persuading a skeptical Congress and an even more skeptical populace to back a military intervention that would cost trillions of dollars and result in the loss of countless lives.

The repercussions of such a monumental intelligence failure extend far beyond the immediate human and financial toll. The flawed rationale for the Iraq War fundamentally reshaped regional dynamics, creating a power vacuum that fueled sectarian violence and gave rise to extremist factions. All of this chaos and carnage stemmed from a single, flawed intelligence report — a high price indeed for the dangers of letting propaganda and erroneous intelligence dictate national policy.

Similarly, the Gambia’s own intelligence community has displayed a disturbing tendency to fabricate stories to suit political ends. Time and again, the intelligence apparatus has proven adept at concocting lies but woefully inept at delivering actionable intelligence.

Recent reports have highlighted a series of intelligence failures that have not only endangered lives but also compromised national security. Much like the botched PsyOps campaign regarding Gen. Bora Colley, these failures reveal a broader problem: a penchant for using intelligence as a tool of manipulation rather than a means of safeguarding the nation.

Herein lies the true danger of turning psychological operations inward. When a military begins to employ tactics of deception against its own people, it is no longer functioning as a protector of the state but as a predator upon it. This is not just a failure of strategy but a profound ethical lapse, a betrayal of the trust placed in them by the people they are sworn to defend.

A military that devotes more time to managing perceptions than addressing real threats ceases to be a military at all; it becomes a pantomime troupe, resplendent in its costumes, strutting and fretting upon the stage of national defence while the nation itself teeters perilously close to the edge.

The Gambia’s intelligence community must heed the costly lessons of the Iraq War and other historical debacles. They must move away from the murky waters of deception and refocus on delivering clear, accurate, and timely intelligence that serves the national interest, rather than short-term political gains.

In other words, if the GAF and their counterparts are serious about protecting the nation, they must commit to transparency and accountability. Only by doing so can they hope to rebuild the trust that has been so recklessly squandered. Until that day comes, the spectre of their own incompetence will loom large — a constant, damning reminder of the dangers of playing fast and loose with the facts.

Setting up Task Force

The absurdity continues with the establishment of yet another “task force” — a phrase that has become synonymous with inaction and obfuscation in the current administration.

Why, pray tell, does the military need to set up a task force to investigate a deserter who has been AWOL for seven years? Does the army really need a committee to conclude that someone who abandons his post and fails to report for duty should face a court-martial and immediate incarceration?

Instead, we have a task force — a fruitless, useless task force that will undoubtedly waste more taxpayer money on what is essentially a wild goose chase. And for what? To pretend that they are doing something — anything — to clean up a mess of their own making.

This government under President Adama Barrow, guided by his motley crew of security advisers, has already wasted millions of dalasis on task forces that have achieved absolutely nothing. It is a tired tactic: when faced with failure, set up a task force. It creates the illusion of action while ensuring that nothing changes.

Like task forces of the past, this one will likely end in predictable fashion: a quiet report that lays blame on no one and quietly files the matter away. Gen. Bora Colley, instead of facing the consequences of his actions, will probably be rewarded with a cushy government job. And all the current security chiefs will remain firmly in their seats, unshaken, unmoved, untouchable.

But what happens when another Bora Colley shows up — not at Fajara Barracks, but at the gates of State House? What happens when the next disgruntled soldier doesn’t come to surrender, but to settle a score? What happens when the guards on duty are not there to arrest, but to be overrun?

Perhaps only then will President Barrow and his security chiefs finally grasp the gravity of their negligence. Perhaps only then will they understand that toying with national security has dire consequences — that the blowback from their complacency and inaction could be catastrophic.

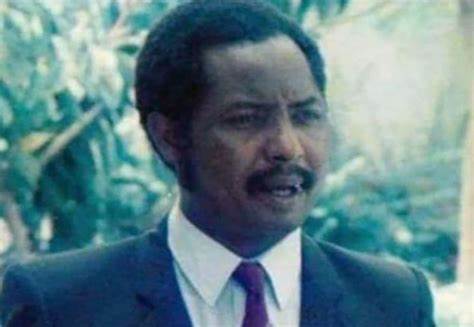

Had they bothered to ask Sir Dawda Jawara, they might have learned a thing or two about the price of complacency. They might have learned that the early warning signs are there for a reason and that ignoring them is a perilous game. As it stands, we can only hope that the lessons of history will not need to be repeated so brutally.

For if another Bora Colley emerges, if another breach occurs, it may very well be the day when the whole house of cards comes tumbling down.

The Gambian Press

The Gambian press, displaying a disturbing gullibility, regurgitates this rubbish without the courage to pen a single editorial shouting down the sheer absurdity of it all. One cannot help but wonder what the likes of Baboucarr Gaye or Deyda Hydara would have made of this ludicrous charade. Were they alive today, they would have undoubtedly ripped into the security forces for their dereliction of duty and their ceaseless efforts to mislead the public.

Imagine, for a moment, the Monday morning edition of The Point newspaper, with its piercing “Good Morning Mr. President” column or “The Bite With DH” biting through the thin veneer of military competence like a knife through butter. Or tuning in to Citizen FM Radio, where no spin doctor or military mouthpiece would be spared from a thorough dressing-down.

The brave and principled journalists of yesteryear would dissect the events with surgical precision, exposing every flaw and every falsehood, leaving no room for ambiguity. They would demand accountability and transparency, traits that are woefully lacking in today’s press corps.

Instead of blandly reprinting official statements, they would have launched a full-scale editorial assault, tearing apart the flimsy excuses and hollow justifications like a pack of wolves descending on a weakened prey.

But alas, the local press today seems more inclined to play the role of the obliging stenographer, reprinting whatever drivel is served up by the army’s PR machine without so much as a raised eyebrow.

Rather than the rousing critiques that would have made the likes of Gaye and Hydara proud, we are treated to a meek parade of articles that seem to ask more questions of the reader than of the military. None of the media houses, it seems, have had the backbone to write an editorial worth a penny on the matter.

The closest we’ve come to any critical scrutiny has been a few scattered articles by folks like Madi Jobarteh. And while Jobarteh’s credentials in the security domain might not hold water among the academic elite, he at least deserves credit for effort.

His analysis may be less academic and more street-level, less sophisticated and more blunt, but at least it is something—an attempt to shine a light on the dark corners where the military would prefer the public not to look.

Who to Blame?

Who, you might ask, is behind this woefully botched attempt at PsyOps, this tragic pantomime of military misinformation? Rather than leave our readers dangling on the edge of a cliffhanger, let us dispense with the mystery and name the culprit outright.

The mastermind — or, rather, the hapless choreographer — of this muddled war of deception is none other than Col. Lamin Sanyang, the head of the GAF’s communications wing. Col. Sanyang, whose statements were once characterised by their clarity and candour, has become a caricature of his former self, more adept now at spinning stories than steering soldiers.

Under his stewardship, the communications wing has devolved into a melodramatic mouthpiece, churning out narratives better suited for tabloid headlines than for the sober dispatches of a national military.

Under his guidance, the communications wing has shifted its focus away from conveying the hard facts and gritty realities of military operations to creating a fictional narrative that attempts to paint over the glaring cracks in the armed forces’ façade.

The press releases are no longer the reliable communiqués of a disciplined army but rather the lurid prose of a tabloid newspaper, filled with half-truths, hyperbole, and the kind of melodrama that would make a Victorian novelist proud.

This descent into tabloid territory is not without consequence. For a military already plagued by inefficiency, disorganisation, and a chronic lack of training, the turn towards sensationalism only serves to distract from the real issues at hand.

During peacetime, the quiet stretches of garrison downtime should be devoted to rigorous training — preparing soldiers for the realities of modern combat, honing their skills in urban warfare, counterinsurgency, and the ever-evolving tactics of hybrid warfare.

Instead, these moments are squandered on rehearsals for the next press conference, with soldiers better trained in the art of holding a microphone than in wielding a rifle.

Military strategists like Sir Lawrence Freedman, in his book Command: The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine, warn of the perils when army leaders dive headfirst into politically driven narratives, noting that an army that loses its strategic focus risks becoming a political pawn, rather than a guardian of national security.

The GAF communication command, under Sanyang’s theatrics, risks falling into this very trap. The army’s shift towards propaganda is not just a dangerous distraction; it undermines the core principles of military discipline and readiness.

Experts like Colonel John Boyd, who is discussed extensively in Robert Coram’s Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War, have long argued that militaries that prioritise image over substance inevitably falter in their primary mission of defence.

Indeed, by engaging in a political sideshow, Sanyang is steering the GAF into treacherous waters where credibility and operational capability are sacrificed at the altar of narrative control.

In a nutshell, it is a tragic irony that a man once seen as a voice of reason has now become the chief architect of confusion, his pronouncements more suited to the front pages of a scandal sheet than the official dispatches of a disciplined military force.

If the GAF continues down this road, they may soon find themselves relegated to the footnotes of history — a stark reminder of the perils of forsaking true military purpose for political theatre.

How About Demilitarisation?

The path forward for The Gambia is clear, though not easy. The current trajectory of the armed forces — one defined by deception, distraction, and disorganisation — must be radically altered.

The nation stands at a crossroads: it can continue to invest in a bloated, inefficient military more adept at parades than at real defence, or it can choose to demilitarise, to redirect its resources towards building a professional, civilian-focused security apparatus that prioritises the safety and well-being of its citizens.

Demilitarisation does not mean the abolition of the military; it means a fundamental rethinking of what role the armed forces should play in a modern, democratic society.

It means reducing the size of the military, reallocating resources towards police, civil defence, and other security agencies better suited to address the real threats facing The Gambia today: crime, terrorism, and civil unrest.

It means shifting the focus from flashy displays of military might to the quiet, steady work of building a resilient society, one capable of withstanding both external pressures and internal divisions.

Countries around the world have embraced demilitarisation with great success. Costa Rica famously abolished its military in 1948 and has since enjoyed a period of sustained peace and prosperity, investing instead in education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

Similarly, Japan, under the constraints of its post-World War II pacifist constitution, has built one of the most advanced economies in the world while maintaining only a Self-Defence Force.

The Gambia, too, can learn from these examples. By demilitarising, it can focus on strengthening its civilian institutions, improving public services, and fostering a culture of transparency and accountability — goals that are all too often at odds with a militarised state.

Ultimately, the decision to demilitarise is a decision to invest in the future of the Gambian people. It is a choice to prioritise their needs over the egos of a few military leaders who have long overstayed their welcome on the stage of national security. It is a choice to build a society where security is defined not by the presence of soldiers on the streets, but by the absence of fear in the hearts of its citizens.

The current state of the GAF is unsustainable. The recent farcical operations, the descent into tabloid-style communications, and the chronic mismanagement of resources all point to a military that is more a burden than a benefit.

It is time for The Gambia to take a bold step towards demilitarisation, to refocus its efforts on building a future where security is achieved not through force, but through fairness; not through intimidation, but through integration; not through bluster, but through true bravery. The people of The Gambia deserve no less.

Experts-Led Reform

Perhaps it’s high time for The Gambia’s national security advisers to shelve their worn-out playbooks of deception and instead delve into the scholarly tomes of Fana Fana intellectuals like Dr. Katim Touray and Dr. Abdoulaye Saine.

Unlike the current cadre of military advisers — who resemble nothing more than amateur actors performing in a poorly rehearsed play — these scholars are seasoned thinkers, comparable to classical Greek philosophers guided by wisdom and not shackled by political paymasters.

They don’t peddle in fanciful fiction or concoct strategic fairy tales to gain favour in high places. Instead, they offer lucidly researched insights into how The Gambia’s military could be reshaped into a formidable force, one that stands not on theatrics but on a foundation of honour and integrity.

Dr. Katim Touray, a well-regarded development consultant and academic, has been advocating for a top-down overhaul of The Gambia’s security setup. His work is a call to arms for transparency, accountability, and a well-defined boundary between military and civilian realms, echoing the core tenets of civil-military relations doctrine.

In his latest piece, “After Yet Another Coup Attempt, It’s Time for The Gambia to Demilitarise,” published in Modern Diplomacy, Touray presents a no-nonsense strategy for military reform.

This includes a bold step towards demilitarisation and a reallocation of military resources to bolster community policing and civil defence. Touray argues that the military needs to slim down from a bloated, archaic machine to a lean, mean security apparatus capable of addressing the real threats facing the Gambian populace (Touray, 2023).

His research lays bare the critical need for transparency, accountability, and a decisive split between military and civilian roles to nurture a robust democratic society.

Meanwhile, Dr. Abdoulaye Saine, a distinguished political science professor, offers a hard-hitting critique of the military’s entanglement in politics through his scholarly work, including the analysis in The Paradox of Third-Wave Democratisation in Africa: The Gambia under AFPRC-APRC Rule, 1994–2008.

Saine’s writings dissect the perils of a military dabbling in governance, exposing how such practices have corroded democratic norms (Saine, 2010). His astute observations highlight the perils of letting soldiers flirt with political power, pulling them away from their sacred duty of defence.

Saine advocates for a civilian-led approach to security, one that fosters a defense strategy built on professionalism, accountability, and strategic prudence (Saine, 2010). His works, praised for their scholarly heft and practical applications, make him a vital voice in the debate on civil-military relations in Africa.

One can almost picture the scene: a group of The Gambia’s military top brass, huddled together in a smoke-filled room, reluctantly flipping through the pages of Touray and Saine’s work, their brows furrowed in confusion as they grapple with concepts like “civilian oversight” and “strategic demilitarisation.”

Indeed, what a sight it would be to see these hardened military men wrestling with the inconvenient truths laid bare by these academics—truths that suggest the very survival of their institution might hinge not on the next big media coup, but on a quiet, thoughtful process of reform and renewal.

It is almost poetic, in a tragic sense, to consider that the salvation of The Gambia’s military might not lie in the machinations of its current leadership, but rather in the dusty tomes of academia — a place where facts are valued over fiction, where reason trumps rhetoric, and where the best path forward is not always the loudest.

If only Col. Sanyang and his colleagues would take the time to read, to learn, and to reflect. Perhaps then, they might realise that the true strength of a military lies not in its ability to deceive, but in its capacity to serve with honour and humility.

In a country desperately yearning for genuine security and stability, the insights of academics like Dr. Touray and Dr. Saine are a much-needed lifeline. Their scholarly calls for reform aren’t just idle chatter from ivory towers; they’re rooted in a rich tradition of philosophical thought that has shaped societies since the days of classical Greece.

Remember Plato and Aristotle? These ancient thinkers didn’t just sit around contemplating the meaning of life — they laid down the blueprint for governance, ethics, and the rule of law. Plato’s vision of philosopher-kings in The Republic and Aristotle’s practical wisdom in Politics weren’t just theories; they were revolutionary ideas that forged civilisations and guided rulers for centuries.

Touray and Saine stand in this grand tradition, their work upholding the timeless wisdom that knowledge and reason must guide the affairs of state. The Gambia’s national security apparatus could do well to heed their advice: put away the cheap tricks of propaganda and embrace a path of genuine reform — one that draws from the well of historical insight and philosophical rigour. Only through such an enlightened approach can the nation hope to achieve lasting peace and true prosperity, not just another fleeting headline.

Final Thoughts

The recent press releases from the GAF high command are less about delivering straightforward communication and more about deploying a carefully orchestrated smokescreen to obscure the truth rather than illuminate it.

The real story here isn’t about the so-called “arrest” or the futile creation of yet another task force. The crux of the issue is the failure to execute even the most fundamental duties that a freshly trained intelligence officer should handle with ease.

This glaring failure lies squarely with the Army’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. How, one must ask, did a high-value target like Bora Colley manage to slip through border security, evade every checkpoint, and saunter into Fajara Barracks without triggering a single alarm?

The answer, inconvenient as it may be, lies in the catastrophic collapse of signals intelligence (SIGINT) and human intelligence (HUMINT) networks. Rather than confronting this colossal failure, the military opted for a classic misdirection, painting a donkey as a racehorse and hoping no one would notice the ruse.

But no amount of rhetorical acrobatics can transform this intelligence debacle into a dazzling success. The “arrest” narrative is a deception tactic, a ruse deployed to distract from the inadequacies of our counterintelligence and early warning systems.

The gambit here is clear: deflect, deceive, and deny, rather than declassify, debrief, and disclose the truth. This attempt at narrative control is as flimsy as the armour on a retired tank, barely masking the glaring gaps in our national defence strategy.

But after all, there is only so long that these theatrics can mask the truth. Eventually, the facade will crumble, revealing the urgent need for genuine reform and competence in securing our nation’s future.

By Arfang Madi Sillah, Washington DC

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institutions or organizations. The author takes full responsibility for the opinions and analysis presented herein. The author holds several academic degrees, including advanced degrees in Intelligence Studies and Military Science.

Recent Comments