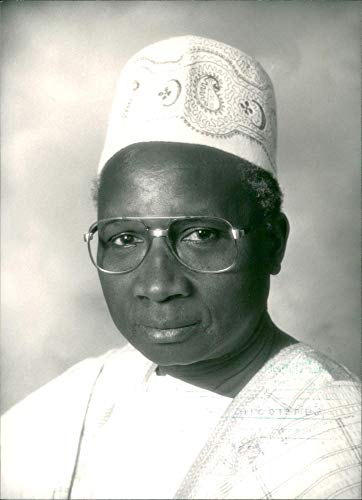

Sadness fell upon me late August when I heard of the death of Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara, former President of The Gambia. The Daily Observer’s article breaking the news in Liberia and narrating the recollections of Kenneth Y. Best refreshed my memory of this soft-spoken man who made invaluable contributions to the peace process in Liberia and whose standard of decency and sense of humanity earned for The Gambia the privilege of becoming the home of the African Centre for Democracy and Human Rights Studies.

I first met President Jawara in Banjul in 1990 when he was Chairman of the Authority of Heads of State and Government (HOSG) of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). I had just been selected to be President of the Interim Government of National Unity (IGNU) by a conference of leaders of Liberian political parties and civil society organizations meeting in Banjul under the auspices of ECOWAS.

The Banjul Conference was part of a larger Peace Plan, the initial draft of which had been proposed by the Inter-Faith Mediation Committee of Liberia. The Plan called for the insertion of a peace keeping force known as the ECOWAS Monitoring Group (ECOMOG) to separate the armed groups and protect the population, and for the formation of a broad-based Interim Government of National Unity (IGNU) in which all armed groups, political parties and civil society organizations would participate. It also called for the holding of elections six months after the insertion of ECOMOG and the installation of IGNU.

We must recall that it was ECOWAS that first intervened in Liberia to stop the carnage and protect the population. The United Nations which is charged with the responsibility to ensure global peace and security was said to be busy trying to end a war that had flared up in the Persian Gulf in 1990 between the United States and its allied forces on one hand and Iraq on the other.

The United States, long considered Liberia’s traditional friend, did not get deeply involved in ending the mayhem and destruction that was taking place in Liberia. So it was left to ECOWAS to take the lead in ending the violent conflict that was consuming Liberia.

Let us also recall that ECOWAS was founded in 1975 with the objective of strengthening economic cooperation among West African Countries. ECOWAS was not established to be a conflict management and resolution body—except for issues connected to economic cooperation among West African states. But ECOWAS had to become seized of the violent crisis in Liberia since neither the United Nations nor the United States would take the lead. So as murder and mayhem reigned in Liberia and fearful citizens could not find safety anywhere, ECOWAS, West Africa’s economic cooperation organization, had to intervene to stop the carnage.

President Jawara had just become Chairman of the ECOWAS Authority when the Liberian crisis picked up intensity. It was he who sounded the alarm that Liberia had become a “slaughter house” and ECOWAS, could not stand idly by and watch the carnage. After considerable consultations, he convened the conference of the armed groups, political parties and civil society organizations of Liberia in Banjul to work out a plan for managing and ending the conflict.

By intervening in Liberia in the absence of any global entity, ECOWAS had, of necessity, shifted the principle of engagement among West African states from the principle of non-interference in the affairs of member-states to the principle of non-indifference to member-states that posed a danger to themselves and their neighbors. Although different in circumstances, Tanzania, a little over a decade earlier, had intervened to stop Idi Amin’s bloodbath in Uganda and its spillover to Tanzania and other parts of East Africa.

Thankfully, the African Union, the successor to the Organization of African Unity, discarded the principle of non-interference in favor of the principle of non-indifference. Lessons from Liberia and other violent crises in Africa had imposed new imperatives on African countries.

I was accompanied by a few Liberian leaders and officials of ECOWAS when I met President Jawara. He had a welcoming smile on his face. He was a modest and dignified man. He looked like someone who was wholly comfortable in his own skin and at peace with himself. His words to us were all about ending the sufferings of the Liberian people, about peace and compassion. Not about politics and power. He emphasized the need for patience and perseverance on the hard road ahead to peace. He assured us of The Gambia’s strong commitment to peace in Liberia and that, as Chairman and thereafter as an ordinary member of ECOWAS, The Gambia would remain committed to ending the sufferings of the Liberian people.

Sir Dawda’s words were soothing. They lowered my anxieties about this uncharted path upon which we had embarked. I told him how thankful we, Liberians, were for his leadership of ECOWAS and for the sacrifices The Gambia was making in supporting the peace process in Liberia. The Gambia had not only played host to the conference; it was also temporarily hosting the organizational secretariat that was coordinating the way forward. I asked him to bear with me and my team as we would always seek his wise counsel and advice.

I informed him that we would like to appoint a resident ambassador who would be consulting him and briefing him on the activities of the Interim Government. He gave his approval. As we left the room, he held my hand. I could feel the warmth of his sincerity and fatherly assurance. A very good man. We later worked out the details with the Foreign Ministry of The Gambia and appointed Professor James Teah Tarpeh as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to The Gambia.

As we undertook consultations around the sub-region and the larger African region, it became necessary to beef up the Liberian Embassy in Nigeria. Ambassador Tarpeh was transferred to Abuja and accredited to Nigeria, ECOWAS, Benin and Togo. James Molley Scott, a career foreign service officer was appointed Liberian Ambassador to The Gambia replacing Ambassador Tarpeh.

The National Patriotic Front rejected the newly organized Interim Government, taking the search for peace from one peace conference to another: from Banjul to Lome (Togo), Bamako (Mali), Yamoussokro (Cote d’Ivoire), Geneva (Switzerland), Cotonou (Benin), Accra (Ghana), Abuja (Nigeria). Several times to Yamoussokro, Cotonou, Accra and Abuja.

At all of the meetings he attended during and after his tenure as Chairman of the ECOWAS Authority, President Jawara remained consistent in his position and compassionate toward the Liberian people who were upper most in his thoughts and actions. Not only did The Gambia contribute troops to the ECOMOG peacekeeping forces; it also provided support in kind to Liberian refugees and to the Interim Government. I remember being so filled with gratitude when Ambassador Tarpeh delivered over a ton of fish, grain and other provisions donated by the Government of The Gambia to the Government of Liberia.

Throughout my tenure as President of the Interim Government of National Unity, I remained close to President Jawara. I recall growing weary and discouraged as we sat through the Yamoussakro series of at least four conferences in 1991 and 1992, chaired by President Felix Houphuet Boigny. President Houphuet Boigny would speak, sometimes for up to an hour, about the importance of “confidence building” and would thereafter adjoin the meeting for lunch or dinner or for good. President Jawara would observe my frustration and would invite me to walk with him back to his hotel suite or villa. We would talk about the session and my frustration. There were times when he would take me into his bedroom and we would sit on his bed talking about how to move the peace process forward and end the violence in a way that would produce lasting peace in Liberia.

Our conversations continued well pass his tenure as Chairman on the ECOWAS Authority. Sometimes our conversations would end on personal notes. On one such occasion in 1993, he asked me, “What would you do when peace comes back to Liberia and you are a free man?” I replied, “I have a standing invitation to return to Indiana University, or I could try to go back to Howard University where I left a job. But my preference is to stay in Liberia and organize a center for supporting the empowerment of women and children and promoting democratic citizenship.” “Mr. President, you should write your memoir,” I respectfully suggested. “I will when I retire,” he responded. “When Sir?” I sheepishly asked. “I have to sort out some internal party leadership issues and then I will retire and someone else will take up the mantle,” he explained. I nodded understandingly.

Before his retirement could occur, Sir Dawda’s government was overthrown in 1994 by a group of soldiers of the Gambian military led by Lieutenant Yahya Jammeh. Sir Dawda went into exile in Senegal. He later settled in Britain.

I was able to reach him several times by telephone when he was in Britain. In the early 2000’s, he paid a visit to the United States and I went to see him in Washington, DC at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. He was delighted to see me. He asked about my family and other Liberians he had gotten to know during the course of his stewardship in the Liberian peace process. We swapped stories of those days and had a good laugh together.

We also talked about his mission to Washington, DC. He explained that he wanted support of world leaders and other influentials so that he would be allowed to return to The Gambia as president with the sole purpose of organizing an orderly democratic transition. His was not a quest for power but a regret that the democratic process of The Gambia had been disrupted and he would like to set it back on course as he left the stage. I told him I had some friends in Washington, DC who could help frame his case. He thanked me and said he had already hired a US-based public relations firm.

I again reminded him about his memoir and volunteered to assist in its preparation, now that I was headed back to Indiana University. Thanks to his faithful assistant, Alex da Costa, his memoir titled, Kairaba,was published in London in 2009.

Sometime in mid-2002, I heard with delight that Sir Dawda had returned home to The Gambia. I did not get in touch with him until several years later. We met in Bamako in 2005 at the African Statesmen Initiative organized by the National Democratic Institute. Present also at that meeting were former Presidents Rawlings and Kufor of Ghana, Nujoma of Namibia, Gowon of Nigeria and Chissano of Mozambique.

We subsequently met in 2006 in South Africa at the Africa Forum of Former Heads of State and Government which was attended by more than 15 former heads of state and government. At every meeting, we would have our moments together. Though his mobility slowed, he remained a wise and much sought after presence in mediation and elections observation on the African continent well into his 80s.

Liberians owe an enormous debt of gratitude to President Jawara for his invaluable contribution to ending the violent conflict that engulfed our country in the 1990s. I am very pleased that the Daily Observer’sarticle honored his memory and also mentioned the very important behind-the-scenes role played by Kenneth Best and Cannon Burgess Carr. Cannon Carr’s passionate plea to the meeting of Heads of State in Banjul in 1990 resonated with many of the attending Heads of State, especially Rawlings and Jawara who told me the story several times.

The Inter-Faith Mediation Committee as a whole must be thanked for stepping up to the urgent call at that time to rescue their country.

Let me also mention the role of two pan-Africanist journalists, Lindsay Barrett and Ben Asante. They were indefatigable in their efforts to build support for the engagement of ECOWAS in Liberia. Liberians also owe them a debt of gratitude.

On Wednesday, September 4th last week, I was privileged to have been on a panel with a number of former presidents of African states at the maiden edition of the Kofi Annan Peace and Security Forum in Accra. In my presentation, I mentioned the contribution of President Jawara in conflict resolution and peacebuilding in West Africa. The audience of over 150 leaders of governments, heads of international organizations and civil society organizations was delighted and massive applauds erupted.

Let us all learn from Sir Dawda lessons of humility, honesty and dignity in service; dedication to service, and respect and empathy for the people we serve.

Thank you, Sir Dawda. Rest in Peace.

By Dr Amos C. Sawyer

Caldwell, Montserrado County

September 10, 2019

Recent Comments