Too many political parties spoil the political broth

Gambian democracy urgently needs repair. We now have a historic opportunity to bring about transformative change. The Elections Act (Decree No. 78, 1996, amended by Act No. 7, 2015) should have been designated as the first reform bill, a top priority for the government of President Adama Barrow.

A reformed and modified Electoral law must respond to twin crises facing our country: the ongoing undermining of electoral democracy — reflected in the formation and registration of a flood of (Taf yengal) peripheral political parties across the country by some (Tangal Cheeb and Sosalasso politicians) — and the urgent demand for defending electoral integrity in the Gambia.

Reform should be based on the critical insight that the best way to defend, support, protect and fix the Gambia’s democracy is to strengthen and restore democracy.

If the Electoral Act amended to reasonable eligibility criteria and procedure over certain thresholds connected to the registration of political parties, it would be the most significant Electoral Law and democracy reform in more than half a century.

The truth of the matter is that many of the political parties registered were unknown to many Gambians. Their political parties were known only by the name of the founder.

Most of the political parties were registered after the Election (Amendment) Act,2015, signed by former President Yahya Jammeh. The democratic era has brought a proliferation of smaller (Taf Yengal political parties) in The Gambia.

However, it has not led to a pluralistic democracy. Democracy induces people to be responsive to the preference of the people. What does the proliferation of registered Sosalasso and Taf Yengal political parties in the Gambia indicate the opposition’s quality?

However, the weakness and instability of the opposition coalition have consequences for political development. Since 2017 the number of registered political parties has multiplied to the Gambia’s democratic experiment. In the Gambia Sosalasso and Taf Yengal, political parties are composed of the wife, the husband, the two children, the maid, and the chauffeur.

There is a lack of national motivation of these smaller parties linked to the inspiration for their creation.

The Department of Justice and the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) mandate in ushering a Third Republic democratic standards. They must be committed to reflecting the views and aspirations of Gambians.

The Gambia needs a new electoral law that will stand the test of time; the Gambian people should recommend reducing the number of political parties in the country.

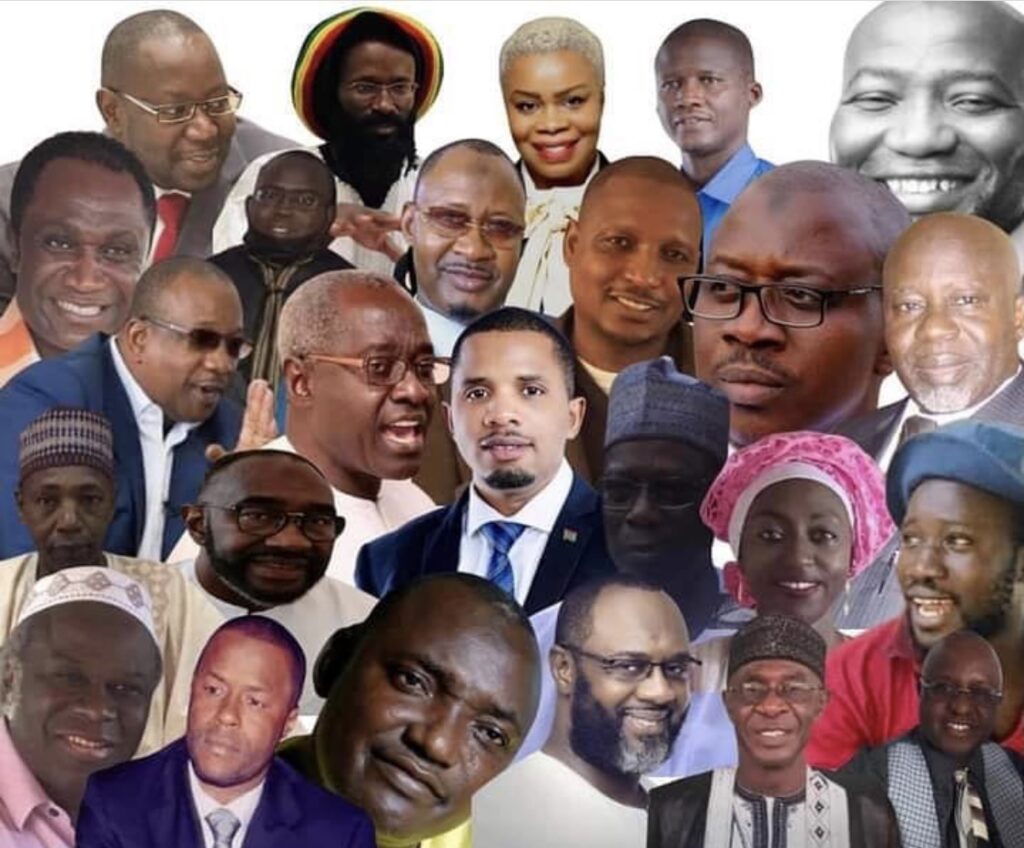

A record number of 18 political parties so far, the highest number ever, and an exponential rise of dynamical complexity of political parties before the December 4 elections are expected.

The extreme partisan proliferation of political parties continued to distort far too many electoral politics manifestations of ideological deficiency and the absence of romantic political inclination in the Gambia.

This plot is poised to be repeated in the upcoming General elections unless the IEC steps to prevent it.

Furthermore, despite increased engagement by small parties from unknown campaign donors, the most expensive campaigns in Gambian history may be primarily bankrolled by a small coterie of individual megadonors and entrenched interests groups, many of whom were able to keep their identities secret from voters.

These problems may be more extreme this election cycle, but they are certainly not new. For decades, citizens’ voices have been silenced through deceptive political tactics. Wealthy campaign donors maintain outsized sway over policy.

Moreover, the guardrails against discrimination, corruption, tribalism and manipulation of the system for personal gain have all been cast aside or eroded.

The current assault on 18 political parties across the country underscores the urgency of reform. However, here is the good news: we know what we need to do to address these problems and strengthen Gambian democracy.

It starts with amending the Electoral Act. The Act must incorporate critical measures that are urgently needed, including campaign loopholes put free and fair elections under threat, steps to modernize our elections; a national guarantee of free and fair elections without voter suppression, coupled with a commitment to restore the full protections of the Electoral Act; instead of big donors (at no cost to taxpayers) and other critical campaign finance reforms; an end to partisan gerrymandering; and a much-needed overhaul of ethics rules.

These reforms respond directly to Gambians’ desire for real solutions that ensure that each of us can have a voice in the decisions that govern our lives, as evidenced by often by lopsided bipartisan margins.

Now, the government and the IEC must also fulfill their promise to secure representative democracy in the Gambia now and for future generations.

However, for a nation with a modest population of 2 million, it is puzzling that we have so many political parties championing “our interests.”

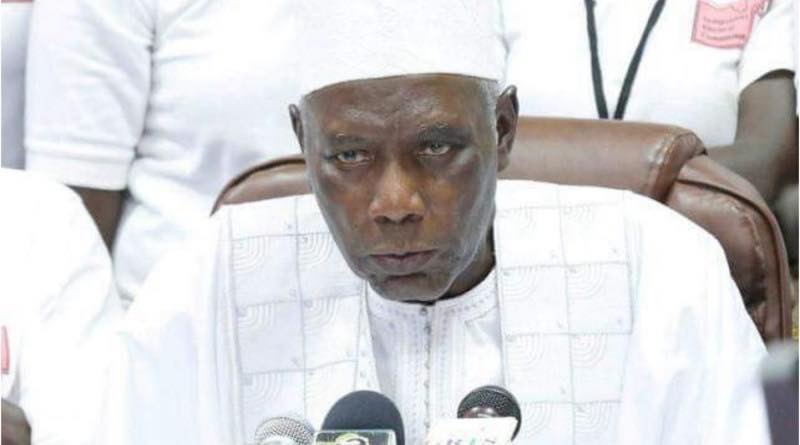

According to the Independent Electoral Commission Chairman Momar, Alieu Njie that some political parties and independents have been registered and regarded as “active” under the Electoral law, and a number on this list of political parties seem to be surviving only by name and lack any authoritarian leadership or organizational structure.

Meanwhile, several others have merged with larger parties, and its existence should be obsolete. The average Gambian would probably be hard-pressed to name even some of these “lesser-known” parties or their leaders; yet, they have managed to continue existing on the fringes of society (A. Y Jallow,2017).

I believed the Gambian people do not need so many political parties, mainly when they only exist for selfish reasons. In a lawful sense, this trend is just a demonstration of individual rights. Freedom of association is and should continue to be an essential hallmark of democracy.

However, we must consider whether an abundance of political parties (especially those formed for selfish reasons) is a positive feature of our electoral politics.

The emergence of many political parties may give the impression of a flourishing multi-party democracy, but when these political parties are no better than special purpose vehicles or briefcase parties to promote a personality or to raise funds and launder money.

Indeed, there should be cause for concern. However, where should the new Constitution and the Electoral Act draw the line?

This question is pertinent in the light of constitutional provisions of section 25 of the 1997 Constitution, which guarantee the freedoms of association, assembly, expression, and belief, critical issues at the heart of the political party formation process.

Those who argue that the more political parties we have, the better also often rely on legal arguments. It is held that the right of association is a fundamental human right.

In the 2021 election, there are already 18 political parties and several prospective parties. According to the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) Chairman, Alieu Momar Njie, in a press briefing stated, “At least 30 requests to form political parties have been received by (IEC)”.

This is my take on too many periphery -center political cleavages in the country. This can create a logistics nightmare and confuse many voters, particularly the less educated during the election.

The paper ballot voting system is set and considered for replacing that antiquated voting system, using the glass marble voting system.

As the Gambia prepares for a momentous 2021 presidential election, there can be no doubt that more political parties would emerge.

For years, Gambian voters have been asking for a system that provides a paper trail. However, is the proliferation of political parties good for our democracy?

The Gambia’s political party system must not be allowed to become a scam, the political equivalent of the notorious 419. Evidence has shown that the giant lottery in the Gambia today is the formation of a political party.

The political parties are also fast becoming like churches and mosques. Anybody raise one million dalasis can set up a political party and use it to raise more funds. You can sell membership cards and tickets to aspiring candidates who need a platform.

You can raise funds online. All you need to do is print a few posters and T-shirts and make as much noise as possible.

You can even at the last moment, step down and declare support for a more prosperous party, join a coalition or alliance and collect a ransom!

This may sound cynical, but that is precisely what is going on in the real sector of the Gambia’s political party system. It is unjustifiable, and it must not be sustained. Once upon a time in the Gambia, we had political parties that were ideas-driven.

In the First Republic, political leaders tried to push ideas. Political leaders were identified with particular ideologies and visions.

Today, many of our political leaders know next to nothing about anything. The naked desperation for power is all that we see on display.

This is shameful in a country that produced Edward Francis Small, Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara, Ibrahima Garba Jahumpa, Sir Pierre Sarr Njie. Where are the visionaries of today? We are, unfortunately, in the age of Godfathers—men who fight over positions and who play God over the fortunes of their compatriots and our country.

We are in the season of mediocrity, incompetence, and opportunism. The salaried career politicians and political hustlers have taken over the Gambia.

However, a political party is a creation of law, and it must be remarked that no right is absolute. The Constitution and the Electoral Act refers to political parties registered based on stipulated rules and guidelines.

Those provisions spelled out in the relevant statutes are not met. Such parties do not live up to the billing of being regarded as political parties.

People who are suggesting the creation of yet another periphery political party have no idea what the challenges of this nation are.

The solution is not in other political cleavages or parties. What you want to ask is, who will be members? Angels from heaven? As long as they will be Gambians, they will slide into our morass. It is certain.

There is nothing wrong with the parties we have, leading political parties. Maybe we need to tighten them up in terms of doctrine and create a clear distinction between them.

Our principal challenge is within us. Our attitude. Our values, or more like the lack of one. We need a significant orientation. An average Gambian, for example, sees a political party as a meal ticket; is this a party or values issue?

We were reaping years of indulgence and bad behavior when we thought we were intelligent and civilized. Today we are all victims of the harvest. You can even see in the past when we had dictatorship.

For less than three years, they would appear like messiahs but would soon slide into the mess covering the rest of the nation.

What remains should the IEC apply the law. However, one must add a caveat here: the de-registration of political parties must not end up as an act of vendetta, witch-hunt, or intimidation.

Any political party de-registered based on performance or violation of the law has every right to re-apply for registration. Should the same political party meet the statutory conditions, and it should be registered afresh.

The rules must be upheld, but at the same time, constitutional rights must be respected. Where does that leave Gambians? We are left with the new Constitution empower the IEC as the regulatory body doing everything possible to respect the rules and thereby deepen the electoral landscape.

The fact that some urgent issues are arising in Gambia’s election will require special attention. The 1997 Constitution is effusive about the campaign finances of political parties.

In tandem with the Election Act, the new Constitution must insist on filtering political parties, annual reports of finances, and political donations.

However, as we know, every election in the Gambia is over-monetized. Those who have the deepest pockets buy the votes and short-change Gambians.

The Constitution is very silent about the use of campaign finance and donations and the integrity of the democratic process. President Barrow has one more general election to conduct: the 2021 general elections. He can either turn it into a legacy event or a source of compounded disgrace. The choice is his to make.

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

Recent Comments