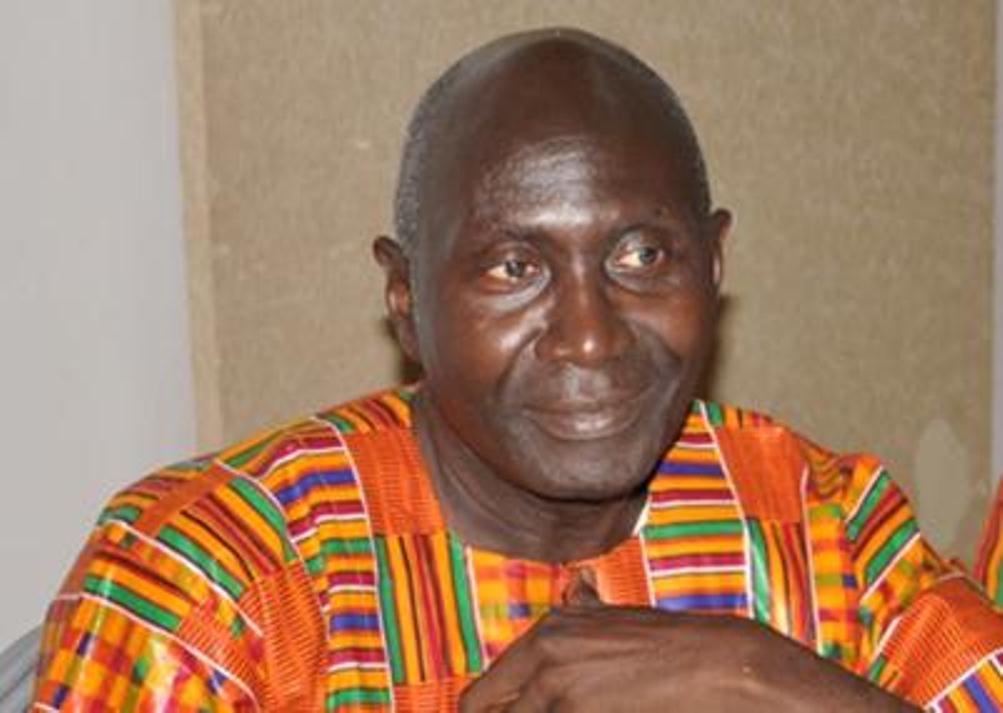

Arfang Madi Sillah, a Washington D.C.-based Gambian scholar and commentator, has written a compelling and thought-provoking book titled The Curtain Falls on the Press and Presidency Relationship—Barrow Goes Berserk.

Known for his incisive political analysis and deep understanding of Gambian affairs, Sillah examines the fraught relationship between the press and the presidency in The Gambia, particularly under President Adama Barrow’s administration.

Below is an abridged version of the book.

Chapter 3: Echo Chambers of Power

In any thriving democracy, the press serves as an indispensable watchdog—a critical force capable of illuminating the darkest corners of governmental malfeasance and holding the powerful accountable.

Journalists, armed with pen and paper—or today, digital devices—are expected to delve deep into the machinations of power, exposing corruption, injustice, and the various ailments that plague society. However, in The Gambia, this noble ideal has been laid to rest, smothered beneath the weight of complacency and co-optation. The media landscape has metamorphosed into a lamentable tableau where newspapers merely regurgitate sanitised narratives churned out by the government’s public relations machine or, worse, fabricate stories out of thin air, relying on phantom sources.

In fact, the last seven years have witnessed an alarming decline in serious investigative journalism in The Gambia, as many editors, reporters, and publishers continue to cash in by selling out instead of selling stories. When was the last time a Gambian minister felt the sweat of panic at the mere mention of their name in print? When was the last time a newspaper headline sent shivers down the spine of those occupying the corridors of power?

The answer, regrettably, is that such moments have become relics of the past. Today, it is not the government trembling in fear of an investigative headline; it is the press itself that seems paralysed, tiptoeing around the truth as if it owes its loyalty to those in power.

The watchdog has become the handmaiden of the very system it was meant to keep in check. Ministers who once feared the wrath of the press now stroll confidently through the corridors of power, knowing full well that the media has been neutered. In other words, the roles have reversed—the government no longer shivers at the thought of the press; rather, the press seems terrified to poke the hornet’s nest of power, acting as though its survival depends on keeping those it should scrutinise firmly out of its crosshairs.

It is a well-established fact in political science that the media plays a pivotal role in shaping public opinion. What the public knows and believes is largely determined by what the press chooses to report—or, increasingly, what it chooses not to report. This is the essence of agenda-setting theory: the power to tell people not what to think, but what to think about.

The role of the press in a democratic society is to serve as a platform for diverse viewpoints and to foster a robust exchange of ideas. Citizens should have free access to the press to exchange ideas, and views should be open to scrutiny because that is how civil society thrives. Yet, in their handling of public debate, mainstream Gambian publications such as The Standard, The Point, The Voice, and FOROYAA have effectively functioned as echo chambers, selectively amplifying the voices of certain individuals while systematically excluding alternative viewpoints.

This editorial censorship has stifled the plurality of voices that is the lifeblood of any vibrant journalistic landscape. It’s as though to appear in the local press, one must possess not just a sound argument but also a secret handshake and the approval of editorial overlords. Whether due to bias, favouritism, or a reluctance to disturb the carefully curated intellectual status quo, the result is a monopoly of ideas where only select voices are amplified. This creates an intellectual bubble that fosters a false sense of invincibility—an environment where critique is unwelcome and dissenting voices are systematically excluded.

We’ve seen similar issues in Britain, where The Guardian has been accused of promoting certain political narratives while sidelining others. Gambian media seems to be following this path, trading intellectual diversity for a comfortable but stagnant intellectual environment.

For years, local newspapers have published the musings of self-proclaimed intellectuals, shielding them from the kind of rigorous scrutiny that is essential for the growth of ideas. Any attempt to offer well-reasoned rejoinders aimed at dismantling these flawed narratives has been conveniently sidelined, never seeing the light of day.

This practice mirrors what George Orwell warned against in Animal Farm: a media environment where certain voices are “more equal than others.” It’s not just about bias; it’s about the erosion of a marketplace of ideas, leaving readers to accept a narrow and unchallenged narrative. By shutting down robust debate and limiting the scope of intellectual engagement, the media has betrayed its duty to the public. They’ve turned the media landscape into a curated platform for the few, leaving readers clutching at straws for a shred of genuine journalism.

This is where the shadow of Dr. Assan Jallow looms large. His long-winded, often incoherent ramblings are given pride of place in the very newspapers that should be holding his ideas to account. It’s not that his ideas are particularly bad; it’s that they’re seldom, if ever, challenged. His recent articles on Dr. Mamadou Tangara were initially published in The Standard, which, as a responsible outlet, should have been the first to offer space for a right of reply to anyone wishing to counter his arguments.

Yet, for some reason, The Standard appears reluctant to publish any counterarguments, almost as if they are shielding these mediocre intellectuals behind some form of editorial protection—akin to paying a kind of “intellectual protection fee.” In this, the state of Gambian journalism is reminiscent of the darker days of British tabloid journalism, where the likes of Richard Desmond, with his scandal-plagued tenure at the Daily Express, turned the media into a playground for the well-heeled and well-connected.

The entire affair reeks of a pay-for-play racket, a betrayal of journalistic principles where coverage can be bought, and editorial stances are up for sale. How can they call themselves independent when they’re more concerned with playing favourites than with serving the public good?

This transformation of journalism into a commodity is exactly what Evelyn Waugh satirised in Scoop, a novel that mocks the absurdities of a press more interested in selling than serving. The Gambian media seems to have embraced Waugh’s satire as a playbook, turning their pages into marketplaces where truth is negotiable.

Dr. Assan Jallow and many of the so-called Gambian intellectuals are prime products of this environment. Scholars who have grown accustomed to having their work published unchallenged are insulated from the peer review process that would otherwise expose the glaring flaws in their reasoning.

In scenarios where these so-called scholars, like Dr. Jallow, make glaring errors or espouse questionable arguments, the mainstream media’s lack of accountability mechanisms ensures that such mistakes go uncorrected, further entrenching the misconception that their work is beyond reproach.

In the past, individuals like Dr. Jallow were able to bask in the glow of unearned intellectual reverence—not because their ideas were particularly insightful, but because the opportunity to critique and challenge their work was systematically denied. Their voices dominated the public sphere simply because opposing voices were silenced by editors who appeared intent on maintaining an intellectual hierarchy where only a select few enjoyed the privilege of being unassailable.

This created a stagnant intellectual landscape where critique was not only discouraged but actively suppressed, resulting in a one-sided discourse devoid of the dynamism and vibrancy that true debate brings.

Evidently, there is an underlying “pay-to-play” dynamic at work, where financial incentives, rather than the merit of ideas, often determine who gets published. This has created an intellectual marketplace where visibility and influence are not earned through rigorous scholarship but purchased through economic means. Such practices undermine the credibility of these media outlets and contribute to the proliferation of unchallenged, substandard intellectual content.

But all is not lost. The growth of independent online platforms is beginning to crack the foundation of this journalistic charade. These digital Davids, armed with laptops and a desire for truth, are challenging the Goliath of mainstream complacency. They’re doing what the traditional press has failed to do—holding the powerful to account, giving voice to the voiceless, and daring to tell the stories that others are too timid to touch. They’re the digital pamphleteers of our time, carrying on the legacy of Thomas Paine, who knew that “the pen is mightier than the sword” only when it’s not sold to the highest bidder.

These digital outlets, dedicated to promoting open debate and diverse perspectives, are exposing the shortcomings of established figures like Dr. Jallow. For the first time, Gambian readers are being presented with a more balanced intellectual landscape, where alternative viewpoints are not only heard but also critically engaged with. This shift is gradually dismantling the illusion of intellectual authority that individuals like Dr. Jallow have long enjoyed, subjecting their ideas to the rigorous scrutiny they have previously evaded.

This emerging trend is reflective of the grand tradition of intellectual inquiry that has shaped human thought from Classical Greece to the Enlightenment era. From the days of Classical Greece, intellectuals like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle championed the value of debate, reason, and—most importantly—the scrutiny of ideas through peer review.

It was their firm belief that truth could only be uncovered through rigorous examination and dialogue, where no thought was considered too sacred or inviolable to be questioned. Socrates, with his relentless dialectical method, engaged his interlocutors in a quest for clearer understanding, always urging them toward greater intellectual humility.

Plato’s Republic epitomises this process, presenting competing arguments that expand the boundaries of knowledge through rigorous debate. Aristotle, not to be outdone, established the Lyceum, where intellectual exchange was not a monologue but a sophisticated dialectic—one that sharpened the minds of all who participated.

Fast-forward to the Enlightenment, and we see philosophers such as Voltaire, Rousseau, and Kant carrying forth the torch of reason, championing free debate not to destroy the views of others, but to refine and develop one’s own ideas through robust critique.

Rousseau’s quarrels with his contemporaries over the nature of human society and Voltaire’s relentless advocacy for free speech were rooted in the conviction that only through contestation could truth be pursued. Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is an enduring testament to the value of challenging and interrogating received wisdom.

The method of peer review—inviting scrutiny to ensure no argument stands untested—has been the linchpin of intellectual progress for centuries. It is this spirit of rigorous inquiry that sustains the advancement of human thought.

The emergence of independent media in The Gambia is thus a return to these fundamental principles of intellectual engagement. By breaking the monopoly of mainstream outlets and allowing a plurality of voices to be heard, these new platforms are reviving the classical tradition of open debate and critical inquiry.

They are ensuring that no idea remains beyond scrutiny and that the truth, however inconvenient, is pursued through rigorous examination. In this new environment, figures like Dr. Jallow can no longer rely on unchallenged platforms to uphold their intellectual stature; they must now engage with their critics and refine their ideas through the very process that has historically propelled human knowledge forward.

The democratisation of information through online media has levelled the playing field, making it increasingly difficult for mainstream outlets to continue their exclusionary practices. In this revitalised intellectual landscape, all ideas—regardless of their source—must withstand public critique and debate. As a result, the Gambian intellectual community is beginning to break free from the constraints of media gatekeeping, paving the way for a more vibrant and dynamic exchange of ideas that honours the timeless tradition of inquiry from Classical Greece to the Enlightenment.

So, let’s not kid ourselves. The mainstream media in The Gambia isn’t about serving the public good; it’s about serving its own interests, peddling influence while pretending to champion the common man. The real heroes are those in the new media, those who dare to challenge the narratives, who refuse to be bought off or intimidated.

And it’s high time the Gambian public stood behind them, because the true battle isn’t between Barrow and the media—it’s between a press that serves itself and a press that serves the people. While the challenges are substantial, the emergence of a more diverse and independent media landscape offers hope that The Gambia can move beyond the dark days of information control and towards a future where the press genuinely serves the public interest.

By Arfang Madi Sillah

To be continued.

See below part one and two of the abridged version of the book.

Recent Comments