Considered the “father of the nation,” Jawara distinguished himself as a modest and deeply religious man, an astute politician and one whose legacy is likely to lie in his commitment to democracy, human rights and rule of law.

This would not have been remarkable were it not for the fact that at independence in 1965, the survival of this ex-colony as a nation was highly improbable (Rice, 1968). Modest government development plans supported initially by British grants, coupled with a pro-Western foreign policy underpinned by a free-market system, inspired international good will and financial support for this West African mini-state (Saine, 2000).

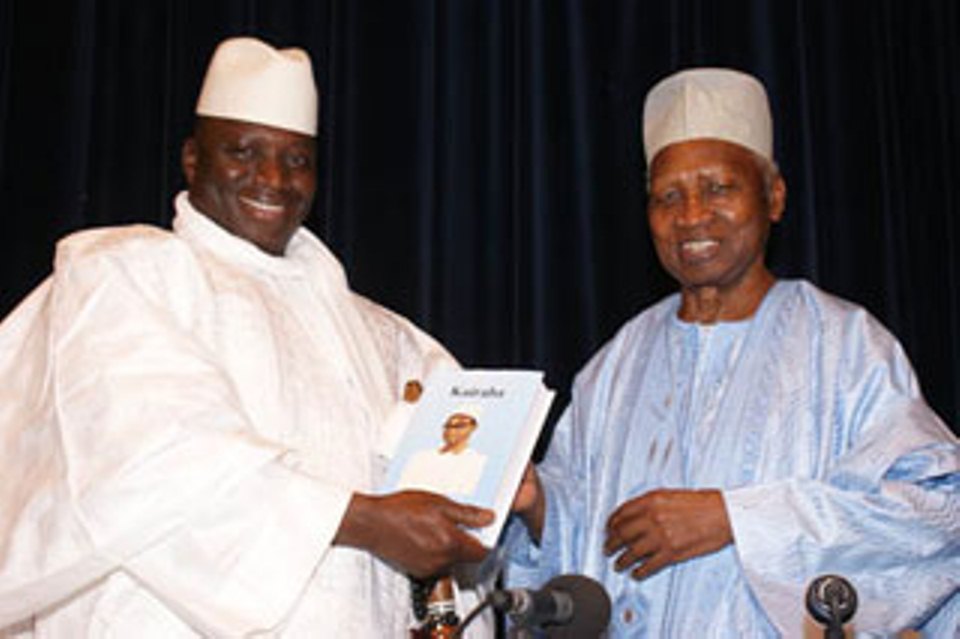

In time, The Gambia and Jawara became practically synonymous, the former enjoying international acclaim for stability and peace and the latter for his unflinching support of peace, human rights and democracy at home and abroad.

The history and political culture of modern Gambia are inextricably tied to and influenced by the life, ideas and personality of Sir Dawda. That The Gambia today remains a sovereign entity owes much to the determination of a man who could have otherwise chosen to live life as a veterinary surgeon looking after the cattle he so adored.

In fact, Jawara was quoted to have said, “There is not a cow in the country that does not know me” (Touray, 1995). Though he did do a great deal for the country, and while his judgment in both his public and personal life was generally sound, he had his faults, however, and is not above criticism. This paper will evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of this father of The Gambia.

Childhood and Early Education

Dawda Jawara was born in 1924 to Almammi Jawara and Mamma Fatty in the village of Barajally Tenda in the central region of The Gambia, approximately 150 miles from the capital, Bathurst. One of six sons, Dawda is lastborn on his mother’s side and a younger brother to sister Na Ceesay and brothers Basaddi and Sheriffo Jawara.

Their father Almammi, who had several wives, was a well-to-do trader who commuted from Barajally Tenda to his trading post in Wally Kunda. Dawda from an early age attended the local Arabic schools to memorize the Quran, a rite of passage for many a Gambian child.

Needless to say, there were no primary schools in Barajally Tenda; the nearest was in Georgetown, the provincial capital, but this boarding school was reserved for the sons of the chiefs.

Yet, as fate would have it, around 1933, young Jawara’s formal education was sponsored by a friend trader of his father’s, Ebrima Youma Jallow, whose trading post was across the street from Alammi’s in Wally-Kunda. Dawda was enrolled at Mohammedan Primary School. After graduation from Mohammedan, Jawara won a scholarship to Boys High School, where he enjoyed all his classes, but showed the greatest aptitude in science and math.

Upon matriculation in 1945, he worked as a nurse until 1947 at the Victoria Hospital in colonial Bathurst. Limited career and educational opportunities in colonial Gambia led to a year’s stint at Achimota College in Ghana, where he studied science. While at Achimota Jawara showed little interest in politics, even when Ghana and many colonies in Africa at the time were beginning to become restless for political independence or internal self-government. While he was happy to have met Ghana’s founding father, Kwame N’Krumah, the impact did not prove significant at the time.

After attending Achimota, Jawara won a scholarship to Scotland’s Glasgow University to study veterinary medicine. This was indeed a remarkable accomplishment for two reasons.

Firstly, it was noteworthy because at the time, colonial education was intended to train Africans for the most menial of clerical tasks in the civil service.

And secondly, it was rare for Gambians to be awarded scholarships in the sciences. It was at Glasgow University in the late 1940s that Jawara’s interest in politics began. In 1948 he joined the African Students Association and was later elected secretary-general and president, respectively.

Also, while at Glasgow, Jawara honed his political interests and skills by joining the Student Labour Party Organization, Forward Group, and became active in labor politics of the time. Though never a “leftist,” Jawara immersed himself in the Labour Party’s socialist politics and ideology. At Glasgow Jawara met Cheddi Jeggan, Guyana’s future “leftist” prime minister, and classified this period in his life “as very interesting politically” (Saine2000). It was a moment of rising Pan-Africanist fervor and personal growth politically. Yet, still a political career was furthest from Jawara’s mind upon completing his studies in 1953.

Return to The Gambia

When Jawara returned home in 1953 after completing his studies as a veterinary surgeon, he served first as a veterinary officer. He became a Christian, and now, as “David,” in 1955 married Augusta Mahoney, daughter of Sir John Mahoney, a prominent Aku in Bathurst. The Aku, a small and relatively educated group, are descendants of freed slaves who settled in The Gambia after manumission.

Despite their relatively small size, they came to dominate both the social, political and economic life of the colony. It was this class that young David Jawara married into. Many opponents claim that it was a pragmatic, albeit an unusual, fulfillment of Jawara’s wish to marry a well-to-do Anglican woman.

As a veterinary officer, Jawara traveled the length and breadth of the Gambia for months vaccinating cattle. In the process, he established valuable social contacts and relationships with the relatively well-to-do cattle owners in the protectorate.

Indeed, it is this group, together with the district chiefs and village heads, who in later years formed the bulk of his initial political support. As indicated previously, British colonial policy at that time divided The Gambia into two sections—the colony and the protectorate. Adults in the colony area, which included Bathurst and the Kombo St. Mary sub-regions, were franchised, while their counterparts in the protectorate were not.

What this meant in effect was that political activity and representation at the Legislative Council were limited to the Colony. At the time of his return to The Gambia, politics in the colony were dominated by a group of urban elites from Bathurst and the Kombo St. Mary’s areas. Needless to say, at a meeting in 1959 at Basse, a major commercial town almost at the end of the Gambia River, the leadership of the People’s Progressive Society decided on a name change, designed to challenge the urban-based parties and their leaders. Thus, was born the Protectorate People’s Party.

In that same year, a delegation headed by Sanjally Bojang, a well-off patron and founding member of the new party, together with Bokarr Fofanah and Madiba Janneh, arrived at Abuko to inform Jawara of his nomination as secretary of the party. Jawara resigned his position as chief veterinary officer in order to contest the 1960 election. In that same year, the Protectorate People’s Party was renamed the People’s Progressive Party (PPP). The name change could not be more timely and appropriate, for it, in principle if not in practice, made the party inclusive as opposed to the generally held perception of it being a Mandinka-based party. Over time, the PPP and Jawara would supersede the urban-based parties and their leaders. This change is what Arnold Hughes termed a “Green Revolution,” a political process in which a rural elite emerges to challenge and ultimately defeat an urban-based political petty-bourgeoisie. Jawara’s political ascendance to the head of the party was hardly contested.

As one of the few university graduates from the protectorate, the only other possible alternative candidate was Dr. Lamin Marena from Kudang (Saine, 2000). In fact, some sources indicated that Marena was the first choice for the post of secretary general, which he declined. Jawara’s origin as a member of the cobbler caste was not looked upon favorably by some within the party and the electorate who claimed to, and in many cases actually did, come from royal background. In time, however, the issue of caste became less important, as the 1960 election results would demonstrate.

Self-Government in The Gambia

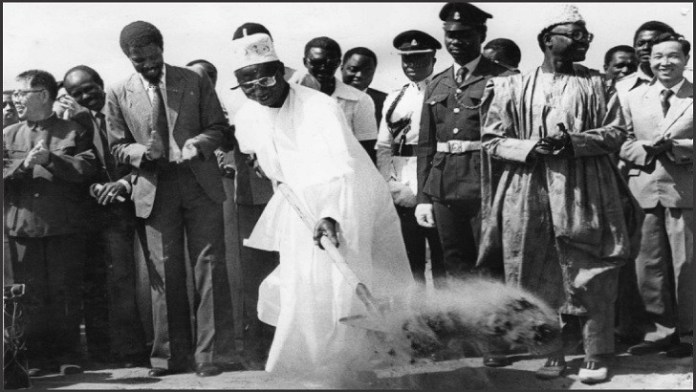

In 1962, Jawara became Prime Minister, which laid the foundation for PPP and Jawara domination of The Gambia’s political landscape. With Jawara’s rise to power after the 1962 elections, the colonial administration began a gradual withdrawal from The Gambia, with self-government granted in 1963. Jawara was appointed Prime Minister in the same year, and independence came on February 18, 1965. This completed The Gambia’s peaceful transition from colonial rule. Yet, independence had its many challenges, as years of colonial neglect left The Gambia with only two government-owned hospitals and high schools and a poor infrastructure.

Unfortunately, The Gambia also faced limited natural resources, a mono-crop export sector and poor social services. At independence, almost all African countries had evolved economies that were extremely vulnerable and heavily dependent on colonial markets and former colonial powers.

Thus, Jawara and his cabinet inherited serious problems that were to influence the subsequent course of politics in The Gambia. With a small civil service, staffed mostly by the Aku and urban Wollofs, Jawara and the PPP sought to build a nation and develop an economy to sustain both farmers and urban dwellers.

Many in the rural areas hoped that political independence would bring with it immediate improvement in their life circumstances. These high expectations, as in other newly independent ex-colonies, stemmed partly from the extravagant promises made by some political leaders.

In time, however, a measure of disappointment set in as the people quickly discovered that their leaders could not deliver on all their promises.

The 1981 Aborted Coup

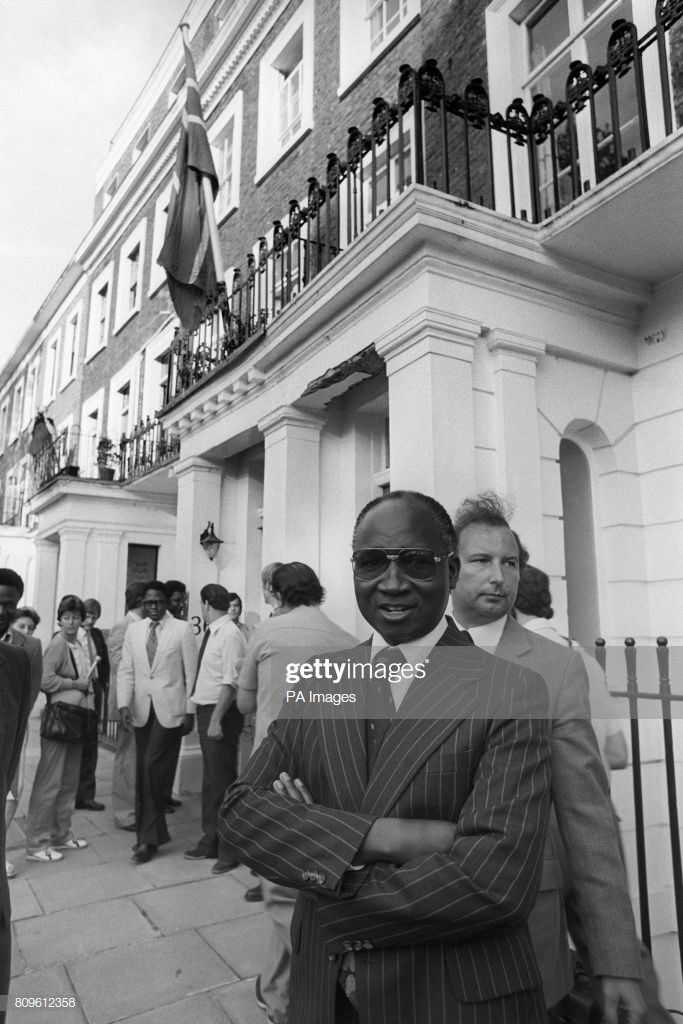

The greatest challenge to Sir Dawda’s rule (other than the coup that ended his power in 1994) was a putsch in 1981, headed by a disgruntled ex-politician turned Marxist, Kukoi Samba Sanyang, and some members of the Field Force (Saine, 1989). The attempted coup reflected the desire for change, at least on the part of some civilians and their allies in the Field Force.

Despite Kukoi’s failure to assume power permanently, the attempted coup revealed major weaknesses within the ruling PPP and society at large. The hegemony of the PPP, contraction of intra-party competition and growing social inequalities were factors that could not be discounted.

Also crucial to the causes of the aborted coup was a deteriorating economy whose major victims were the urban youth in particular. In his 1981 New Year message, Jawara explained The Gambia’s economic problems thus:

“We live in a world saddled with massive economic problems. The economic situation

has generally been characterized by rampant inflation, periods of excessive monetary

instability and credit squeeze . . . soaring oil prices and commodity speculation. These

worldwide problems have imposed extreme limitations on the economies like

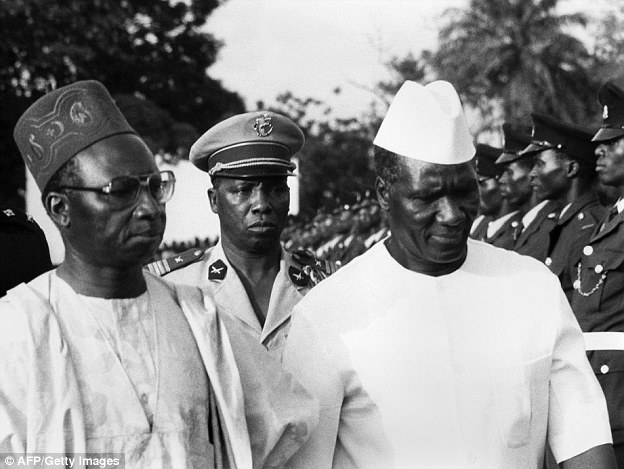

The Gambia” (Sallah, 1990).The most striking consequence of the aborted coup was the intervention of the Senegalese troops at the request of Jawara, as a result of the defense treaty signed between the two countries in 1965. At the time of the aborted coup Jawara was attending the wedding of Prince Charles and Princess Diana in London and flew immediately to Dakar to consult with President Abdou Diouf. While Senegal’s intervention was ostensibly to rescue President Jawara’s regime, it had the effect of undermining The Gambia’s sovereignty, which was something that had been jealously guarded by Gambians and Jawara in particular. Yet it was relinquished expediently. The presence of Senegalese troops in Banjul was testimony to Jawara’s growing reliance on Senegal, which consequently was a source of much resentment against him and his government.

The Senegambian Confederation

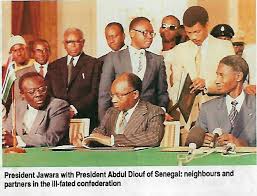

Just three weeks after the aborted coup and the successful restoration of Jawara by Senegalese troops, Presidents Diouf and Jawara, at a joint press conference, announced plans for the establishment of the Senegambian Confederation. In December 1981, five months after the foiled coup, the treaties of confederation were signed in Kaur. The speed with which the treaties were signed and the lack of input from the bulk of the Gambian population suggested to many that the arrangement was an exercise in political expedience.

Clearly, President Jawara was under great pressure because of the repercussions of the aborted coup and from the Senegalese government. Under the agreements with Senegal, President Diouf served as president and Sir Dawda as his vice. A confederal parliament and cabinet were set up with several ministerial positions going to The Gambia. Additionally, a new Gambian army was created as part of a newly confederate army.

The creation of a new Gambian army was cause for concern for many observers. Such an institution, it was felt, would by no means diminish the reoccurrence of the events of July, 30, 1981, nor would it guarantee the regime’s stability. By agreeing to the creation of an army, Jawara had unwittingly planted the very seeds of his eventual political demise.

The army would in time become a serious contender for political office, different from political parties only in its control over the instruments of violence.

Therefore, it seems likely that Jawara had few if any other option but to create a new Gambia army. Such an atmosphere, however, as the events of 1994 would show, was fertile ground for coups and counter coups.

Perhaps more important, the creation of a new army diverted limited resources that could have otherwise been used to enhance the strong rural development programs of the PPP government. The Confederation eventually collapsed in 1989.

Jawara did not resort to the authoritarian and often punitive backlash that follows coups in most of Africa. Instead, he made overtures of reconciliation, with judicious and speedy trial and subsequent release of well over 800 detainees. Individuals who received death sentence convictions were committed to life in prison instead, and many prisoners were released for lack of sufficient evidence.

The trial of more serious offenders by an impartial panel of judges drawn from Anglophone Commonwealth countries is testimony to Jawara’s democratic impulses, sense of fair play and respect for human rights. International goodwill toward the regime was immediate and generous and before long Jawara had begun a process of political and economic reconstruction of the country. Thus, it would have been premature to dismiss democracy in The Gambia at that time.

The Politics of Economic Reform

One of the most marginal nations in the capitalist periphery at the time of independence, The Gambia was incorporated into the world capitalist system as a supplier of agricultural exports (largely groundnuts) and tourism. Since independence, there has been little change in the structure of the economy, which remains very heavily dependent on groundnut production.

Agriculture and tourism are the dominant sectors and also the main sources of foreign exchange, employment, and income for the country. Thanks to the growing economy, the government introduced in the 1970s the policy of Gambianization, which led to an expansion of the state’s role in the economy. There was a 75 percent increase in total government employment over the period from 1975 to 1980.

In mid-1985, The Gambia under Jawara initiated the Economic Recovery Program (ERP) (McPherson, 1995), one of the most comprehensive economic adjustment programs devised by any country in sub-Saharan Africa. With the aid of a team of economists from the Harvard Institute for International Development and the International Monetary Fund, The Gambia greatly reformed the economic structure of the country. Under ERP, in 1985-86, the deficit was 72 million Dalasis, and it increased to 169 million Dalasis in 1990-91 (Budget Speech, June 15, 1990). However, by mid-1986, just a year after the ERP was established, the revival of The Gambian economy had begun. The government reduced its budget deficit, increased it foreign exchange reserves, and eliminated it debt service arrears.

Under the ERP, money-seeking opportunities became more abundant, and, unfortunately, many private businessmen and public officials turned to illegal means to make profit. Corruption created a serious legitimacy crisis for PPP. Several cases of corruption were revealed, and these seriously indicted the PPP regime.

The Gambia Commercial Development Bank collapsed, largely due to its failure to collect loans. An Asset Management and Recovery Corporation (AMRC) was set up under an act of parliament in 1992, but the PPP government was not willing to use its influence to assist AMRC in its recovery exercise.

This was particularly embarrassing because of the fact that the people and organizations with the highest loans were close to PPP. In an embezzlement scheme at the Gambia Cooperative Union (GCU), fraud was revealed in Customs (McNamara and McPherson 1995), and through the process of privatization, it was discovered that many dummy loans had been given to well-connected individuals at GCDB (McPherson and Radelet, 1995).

A group of parastatal heads and big businessmen closely associated with the PPP (nicknamed the Banjul Mafia) were seen as most responsible for corruption in the public sector (Sallah, 1990). Driven to make profit, many elites did not refrain from manipulating state power to maintain a lifestyle of wealth and privilege. Corruption had become a serious problem in The Gambia, especially during the last two years of the PPP rule.

By 1992, The Gambia was one of the poorest countries in Africa and the world, with a 45-year life expectancy at birth, an infant mortality rate of 130 per 1000 live births, a child mortality rate of 292 per 1000, and an under-five mortality rate of 227 per 1000. At that time, 120 out of every 1000 live births died of malaria.

The Gambia also had a 75 percent illiteracy rate, only 40 percent of the population had access to potable water supply, and over 75 percent of the population were living in absolute poverty (ECA, 1993).

Structural adjustment programs implemented in response to the economic crisis resulted in government fragmentation, privatization, less patronage in co-opting various groups and growing corruption. The 30-year PPP regime operated with diminished resources and therefore could no longer rule as it always had.

The credibility of the competitive party system was severely challenged as Jawara’s PPP was unable to show that good economic management could lead to benefits for the majority of society.

To combat the myriad threats to political survival, a leader needs resource. Despite the existence of both state- and time-specific variations, it is possible to identify a range of resources leaders may employ to prolong their rule. African leaders have access to two types of resources: domestic (by virtue of their access to the state) and external (foreign aid, loans, and so forth).

Given states’ widely disparate levels of domestic resources, with some possessing valuable mineral deposits and others confined to agricultural production, generalizations are unwise, although an accurate case-by-case assessment of a leader’s domestic resource base is clearly an important factor when explaining political survival.

Regime Survival in The Gambia

In the Gambia the PPP regime’s prolonged survival owed much to its leader. There existed an intimate, almost inextricable link between the survival of Dawda Jawara and the survival of the regime, Jawara’s apparent indispensability reflected his uncommon ability to maintain subordinate’s loyalty without forfeiting popular support. Jawara’s rule created and sustained a predominant position within the PPP.

With Jawara’s precarious hold on power at independence, his low caste status constituted a grave handicap and one which threatened to overshadow his strengths (most notably, a university education). The two pre-independence challenges to Jawara’s position demonstrated his vulnerability and illustrated the fact that he could not rely upon the undivided loyalty of the party’s founding members.

At independence Jawara’s lieutenants regarded him as their representative, almost a nominal leader, and clearly intended him to promote their personal advancement.

Given these circumstances, Jawara’s task was to overcome his low caste status, assert his authority over the party and secure control over its political direction. In doing this, he did not use coercion. Politically inspired “disappearances” were never an element of PPP rule; neither opponents nor supporters suffered harassment or periods of detention on fabricated charges.

That Jawara was able to eschew coercive techniques and still survive reflected an element of good fortune, and yet his skillful political leadership was also crucial. Within his own party Jawara was fortunate to be surrounded by individuals willing to refrain from violence to achieve their goals, and yet much of the credit for this restraint must go to Jawara—his skilful manipulation of patronage resources, cultivation of affective ties and shrewd balancing of factions within the PPP.

Lacking the coercive option, and given that affective ties, which had to be earned, were a medium- to long-term resource, Jawara initially relied heavily on instrumental ties and distribution of patronage. His limited resource base posed an obvious, though not insurmountable, problem. Within the ruling group, ministerial positions—which provided a generous salary, perks and for some, access to illicit wealth—constituted the most sought-after form of patronage and yet, before 1970, the number of ministerial posts did not exceed seven.

By 1992 the number remained a comparatively modest fourteen. Despite these limits, Jawara skillfully used all the various permutations of patronage distribution (appointment, promotion, termination, demotion and rehabilitation) to dramatize his power over subordinates’ political futures and entrench himself as leader.

After independence, in response to the pre-1965 challenges to his authority, Jawara moved to reduce the size, cohesion and authority of the founding members as a group. Many of the party’s earliest adherents (even those who showed no outward sign of disloyalty) lost ministerial posts during the early years of PPP rule. Jawara may not have used force, but neither was he hampered by sentiment; his pragmatism and willingness to demote, or even drop, former supporters in order to strengthen his personal political position was apparent.

Jawara further strengthened his political position with the incorporation of new sources of support within the ruling group. His enthusiasm for political accommodation stemmed from the closely related imperatives of weakening the influence of the PPP’s original members and avoiding political isolation. The original group resented the fact that newcomers had not participated in the early struggle for power and yet were now enjoying the fruits of their labour.

The secondary factor of ethno-regional considerations compounded this resentment; those who were co-opted came from all ethnic groups in the former colony and protectorate.

Jawara’s popular support and cultivation of effective ties were crucial for easing the pressure on scarce patronage resources. Although the skilful distribution of patronage and associated tolerance of corruption (to be discussed later) played an important role in the PPP’s survival, Jawara did not rely on elite-level resource distribution as heavily as some of his counterparts.

By Alagi Yorro Jallow

One Comment